Pierre Boulez, compositeur, pédagogue et transmetteur

Sur la base d’un entretien croisé avec Katharina Rengger, flûtiste et pédagogue qui fut de 2000 à 2011 la responsable de projet de l’Académie du Festival de Lucerne sous la direction artistique de Pierre Boulez, Jonathan Goldman, musicologue qui a consacré de nombreuses recherches au compositeur, et Frank Madlener, directeur de l’Ircam, nous tentons d’appréhender les contextes qui ont favorisé une transmission destinée plus spécifiquement aux compositeurs et compositrices.

Sur la base d’un entretien croisé avec Katharina Rengger, flûtiste et pédagogue qui fut de 2000 à 2011 la responsable de projet de l’Académie du Festival de Lucerne sous la direction artistique de Pierre Boulez, Jonathan Goldman, musicologue qui a consacré de nombreuses recherches au compositeur, et Frank Madlener, directeur de l’Ircam, nous tentons d’appréhender les contextes qui ont favorisé une transmission destinée plus spécifiquement aux compositeurs et compositrices.

Stravinsky et Schoenberg, dont on sait avec quelle radicalité les a opposés Adorno, peuvent aussi, comme le suggère Jonathan Goldman, apparaître incidemment comme des curseurs – le premier n’ayant jamais approché l’enseignement, le second y ayant consacré une large part de son existence – entre lesquels se situerait Pierre Boulez dans sa pratique pédagogique. La position du compositeur sur l’enseignement a été à plusieurs reprises formulée dans ses écrits. Elle tend à rapprocher, sinon assimiler, comme le souligne Jonathan Goldman, l’enseignement de la composition de celui de l’analyse, et si l’on peut voir dans cette attitude l’influence du modèle de Messiaen, elle révèle également une volonté de centrer l’enseignement sur l’élève, qu’il s’agit de révéler musicalement à lui ou elle-même par la confrontation à l’autre. Dans une conférence donnée à Darmstadt en 1961, Boulez esquisse, après avoir reproché aux conservatoires « la transmission héréditaire d’un certain nombre de tabous », le profil de l’enseignant idéal. Il souhaite à ses élèves « qu’ils arrivent à ce que les maîtres d’une génération précédente leurs parlent d’eux » mais se positionne contre la libéralité, car « le maître doit susciter un doute fondamental et une insatisfaction permanente »1

« La pédagogie, pour moi, a représenté un choc. Et je crois qu’elle doit être un choc. »

Pierre Boulez

Dès les années 50, il exprime son scepticisme envers « la pédagogie à partir d’un certain niveau », qu’il tempère cependant par l’« extrême importance » qu’il attache à « la rencontre des personnalités », susceptible d’apporter davantage que l’enseignement proprement dit. À plusieurs reprises pendant sa carrière de pédagogue, il insistera sur les limites temporelles souhaitables de cette rencontre : « Chez Messiaen, j’ai trouvé encore, fait beaucoup plus rare, la compréhension de cette déchirure qui doit séparer maître et élève, une fois le temps d’apprentissage écoulé. »2

C’est pendant la période où il enseigne la composition à la Musik-Akademie de Bâle, entre 1961 et 1963, que Boulez peut réellement approfondir cette pratique, même s’il reconnaîtra rétrospectivement ne l’avoir « pas fait avec grand enthousiasme. »3 Son enseignement repose sur la complémentarité d’une classe d’analyse et d’un cours de composition, le second dispensé à un petit groupe d’élèves. L’analyse qu’il défend est une analyse personnelle et créative, et son apport en matière de composition repose quant à lui sur des exercices concrets. Suivant l’idée maîtresse de son propre rapport à la composition, il s’agit ici pour Boulez d’apprendre à ses élèves à développer, à déduire. Dans un entretien avec Philippe Albèra, il évoque cette approche pédagogique : « je donnais un certain matériel aux étudiants, en leur demandant de le développer, et je le développais moi-même de mon côté. Après un mois, nous regardions ce que chacun avait déduit des structures initiales. »4

C’est pendant la période où il enseigne la composition à la Musik-Akademie de Bâle, entre 1961 et 1963, que Boulez peut réellement approfondir cette pratique, même s’il reconnaîtra rétrospectivement ne l’avoir « pas fait avec grand enthousiasme. »3 Son enseignement repose sur la complémentarité d’une classe d’analyse et d’un cours de composition, le second dispensé à un petit groupe d’élèves. L’analyse qu’il défend est une analyse personnelle et créative, et son apport en matière de composition repose quant à lui sur des exercices concrets. Suivant l’idée maîtresse de son propre rapport à la composition, il s’agit ici pour Boulez d’apprendre à ses élèves à développer, à déduire. Dans un entretien avec Philippe Albèra, il évoque cette approche pédagogique : « je donnais un certain matériel aux étudiants, en leur demandant de le développer, et je le développais moi-même de mon côté. Après un mois, nous regardions ce que chacun avait déduit des structures initiales. »4

Au-delà de ces exercices thématiques, Boulez est confronté à des œuvres que lui soumettent ses élèves, situation particulièrement inconfortable car « en dehors des maladresses et des malfaçons » dont il peut faire le constat, l’enseignant « se trouve cantonné dans une position exclusivement personnelle », où « il n’a que sa mémoire ou son savoir-faire à opposer à l’objet qu’on lui présente », et où « l’enseigné pourra tout au plus constater l’égocentrisme de l’enseignant, ce qui ne lui apprendra […] rien de véritablement utile. »5 Si Boulez continue en 1996, lors d’un colloque qui se tient à l’Ircam, à se demander s’il est possible de « transmettre, guider ou argumenter la créativité »6, il se questionne également sur l’influence que peut avoir sur sa propre créativité le contenu de ce qu’il transmet, voire le fait même de cette transmission. On peut supposer la réponse positive lorsqu’il affirme : « La pédagogie, pour moi, a représenté un choc. Et je crois qu’elle doit être un choc. »7

Bien sûr, Boulez a eu au préalable l’occasion de formaliser, mais de façon plus théorique, un enseignement sous la forme du cycle de conférences Penser la musique aujourd’hui tenu à l’été 1960 aux Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik de Darmstadt, qui a donné lieu à l’ouvrage éponyme. En outre, à la même époque où il enseigne à Bâle, il est nommé conférencier invité à Harvard pour les années 1962-63. Cet enseignement pointu mais néanmoins destiné à un public élargi préfigure dans une certaine mesure celui qu’il dispensera de façon bien plus développée au Collège de France de 1977 à 1995, en tant que titulaire de la chaire « Invention, technique et langage ».  Là, Boulez s’adresse à la fois à un public cultivé et expert et à des non spécialistes. Comme le fait remarquer Jonathan Goldman, les publications issues de ces cours – d’abord Jalons pour une décennie (1989) puis Leçons de musique (2005) – ne comportent pas d’exemples musicaux.

Là, Boulez s’adresse à la fois à un public cultivé et expert et à des non spécialistes. Comme le fait remarquer Jonathan Goldman, les publications issues de ces cours – d’abord Jalons pour une décennie (1989) puis Leçons de musique (2005) – ne comportent pas d’exemples musicaux.

C’est à un enseignement beaucoup plus concret que souhaite se consacrer Boulez lorsqu’il fonde en 2004 l’académie du festival de Lucerne, qu’il dirige chaque été jusqu’en 2015. Katharina Rengger, responsable de la mise en œuvre du projet et de son suivi, en rappelle la structure : « À l’académie, le noyau dur était l’orchestre, pour lequel nous construisions des programmes de concerts autour desquels s’articulaient deux projets vraiment importants : la masterclass de composition, qui s’adressait à de jeunes chefs et cheffes travaillant sur le répertoire du moment, et le travail avec les compositeurs. Par voie de concours, nous choisissions tous les trois ans deux compositeurs, Pierre Boulez jouant un rôle majeur dans leur sélection. » Les deux premiers compositeurs à avoir participé à l’académie sont Dai Fujikura et Christophe Bertrand, les deux suivants Ondrej Adámek et Johannes Boris Borowski, tous les quatre guidés et soutenus par Boulez, comme le remarque Jonathan Goldman, au-delà de ce cadre académique.

Katharina Rengger insiste sur le triangle formé par les compositeurs et compositrices, les chefs et cheffes et les jeunes instrumentistes de l’orchestre, dont les échanges intenses et la collaboration créent une situation d’apprentissage mutuel. L’organisation triennale de l’académie inscrit cette relation dans le long terme, la création des pièces commandées au terme du cycle étant précédée, outre les réunions pluriannuelles au cours desquelles « Boulez donnait des conseils et surtout questionnait les compositeurs, suggérant par ce questionnement de nouvelles directions », de séances d’essai pendant l’académie. Là, ils « dialoguaient avec les membres de l’Ensemble Intercontemporain et les jeunes musiciens et musiciennes de l’académie, ce qui leur donnait l’occasion de confronter leurs esquisses avec l’expérience réelle des interprètes ». Dai Fujikura et Christophe Bertrand, qui avaient reçu une commande pour 2005, ont pu ainsi tester leurs ébauches lors de l’académie 2004.

Katharina Rengger se souvient que la teneur de ces échanges n’était jamais dogmatique, et qu’« efficacité » était le maître mot de ces sessions. « Boulez était infatigable, faisant tout pour rendre ces trois semaines très riches, ouvert à de nombreuses questions qui se prolongeaient après les répétitions, et dont il semblait bénéficier lui-même comme d’une source de rajeunissement ! » Selon elle, les moments les plus intéressants se manifestaient pendant les concerts « Forum », qui offraient au public un aperçu du processus d’élaboration, car à cette occasion, sa transmission allait évidemment vers les jeunes chefs et cheffes mais aussi vers le public, à qui il s’agissait de faire prendre conscience des enjeux de la direction.

C’était là une autre composante de son travail pédagogique qui, selon Frank Madlener, constitue un point commun entre « son attitude envers les compositeurs et compositrices, ses interlocuteurs et interlocutrices et le public : une sorte de maïeutique consistant à faire accoucher la personne de ce qu’elle a à dire. »

« Boulez était infatigable, faisant tout pour rendre ces trois semaines [d’académie] très riches, ouvert à de nombreuses questions qui se prolongeaient après les répétitions, et dont il semblait bénéficier luimême comme d’une source de rajeunissement ! »

Katharina Rengger

Faisant en sorte que la question vienne de nous-mêmes, que l’on « s’émancipe de tout professorat, il établit une forme de didactisme intelligent qui se manifeste même dans sa forme de direction, consistant à faire apparaître les choses. » Frank Madlener y voit là « un effet socratique qui ramène toujours à une même attitude, celle de l’émancipation par rapport au modèle. » Pour lui, de la même façon que « la direction de Pierre Boulez est explicite, montre et donne à entendre », certaines de ses œuvres sont aussi « un acte rhétorique ». Selon lui, « Répons démontre la nécessité de l’électronique en temps réel, Éclat constitue une rhétorique de la résonance et montre aussi le pouvoir du chef ou de la cheffe puisque la temporalité dépend de la résonance. »  De même, ajoute Jonathan Goldman, « Domaines, où le clarinettiste se déplace pour se joindre à différents sous-ensembles, rend visible la forme de l’œuvre par sa trajectoire ».

De même, ajoute Jonathan Goldman, « Domaines, où le clarinettiste se déplace pour se joindre à différents sous-ensembles, rend visible la forme de l’œuvre par sa trajectoire ».

Le musicologue rappelle l’influence décisive qu’a pu avoir sur Boulez, en matière de pédagogie, le modèle du Bauhaus. Celle-ci se manifeste à plusieurs niveaux, dont le plus immédiat est irrigué par le contenu même de l’enseignement de Klee : « Tout le génie de Klee est là : partir d’une problématique très simple et parvenir à une poétique d’une force remarquable où la problématique est totalement absorbée. […] Pour moi, c’est la plus grande des leçons : ne pas craindre de réduire parfois les phénomènes de l’imagination à des problèmes élémentaires, “géométrisés” en quelque sorte. La réflexion sur le problème, sur la fonction, amène la poétique à acquérir des richesses qu’elle n’aurait pas même soupçonnées si l’on n’avait fait que laisser libre cours à l’imagination. »8 Mais au-delà de cette convergence artistique et de l’admiration de celui chez qui « la pédagogie n’a fait qu’enrichir l’invention »9, c’est aussi sur la conception de l’Ircam que se projette le modèle du Bauhaus.

L’institut, ainsi que l’a relevé Hugues Dufourt, en reprend le projet d’une pédagogie, « entendue comme coopération entre artistes, éducation aux techniques de l’art et activité didactique à grande échelle. »10Le créateur d’institutions qu’est Pierre Boulez semble toujours y entrevoir une fonction pédagogique, et ceci vaut aussi pour l’Ensemble Intercontemporain. Jonathan Goldman rappelle à ce sujet que « dans les années 80, Boulez dirigeait des concerts-ateliers dont les programmes étaient conçus pour mettre en valeur, indépendamment de ses goûts personnels, des œuvres qu’il considérait comme des documents importants pour l’histoire de la musique. »

Le périmètre sur lequel il a pu étendre son action de transmission est vaste. Pierre Boulez aurait cependant souhaité l’élargir davantage encore. « À la fin de sa carrière et de sa vie, témoigne Frank Madlener, quand il repensait à Lucerne et à l’académie, il disait que s’il devait encore faire quelque chose aujourd’hui, ce serait enseigner la direction artistique », manifestement préoccupé par la standardisation des programmes. On n’a pas fini d’évaluer son héritage, un « héritage précédé d’aucun testament » pour reprendre la formule de René Char.

Par Pierre Rigaudière

![]()

1. Pierre Boulez, « Discipline et communication », dans Points de repère, vol. I, textes édités par Sophie Galaise et Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Bourgois, 1995, p. 384 et 389.

2. Pierre Boulez, « Le maître », dans Points de repère, vol. I, p. 463.

3. Pierre Boulez, « L’instant et l’étendue » (1996), dans Peter Szendy, Enseigner la composition, cahiers de l’Ircam, 1998, p. 141.

4. Philippe Albèra, « Entretien avec Pierre Boulez », dans Pli selon pli de Pierre Boulez, Genève, Contrechamps, 2003, p. 11.

5. Pierre Boulez, « Mémoire et création » dans Leçons de musique – Points de repères, vol. III, textes édités par Jean-Jacques Nattiez et Jonathan Goldman, 2005, Bourgois, p. 526.

6. Pierre Boulez, « L’instant et l’étendue », p. 135.

7. Ibid.

8. Pierre Boulez, « Le pays fertile », dans Points de repère, vol. II, textes édités par Sophie Galaise et Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Bourgois, 2005, p. 760.

9. Ibid., p. 761.

10. Hugues Dufourt, « Le Bauhaus et l’Ircam : deux “maisons de la construction” au XXe siècle, in Szendy, p. 107.

![]()

Photo 1 : Pierre Boulez, février 2009 à Salzbourg © Le regard de James, Jean Radel

Photo 2 et 3 : Pierre Boulez et Le Lin, Concours international Olivier Messiaen, décembre 2007 © Ircam-Centre Pompidou, photo : Éric de Gélis

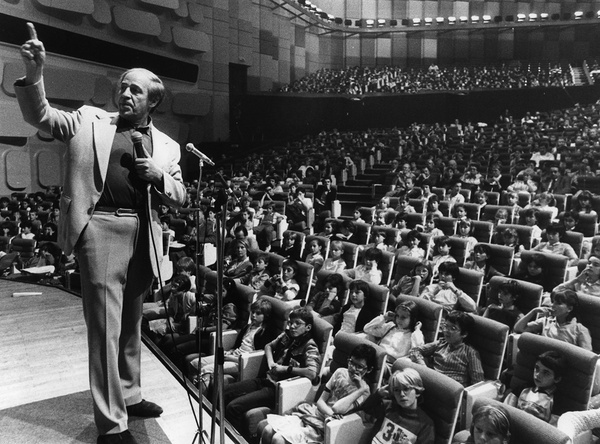

Photo 4 : Pierre Boulez, concert scolaire, 1983 © B. Meyer

Photo 5 : Pierre Boulez et une partie des musiciens de l'Ensemble intercontemporain, mars 2009 à Anvers © Le regard de James, Jean Radel