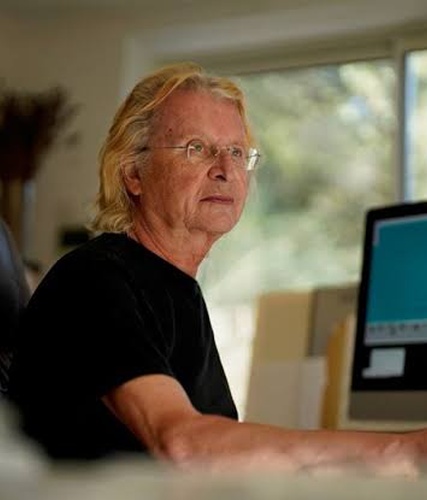

Tristan Murail en studio

Tribulations musicales - Enjeux artistiques

Le Livre des merveilles, connu aussi sous le titre de Devisement du monde, c’est le récit, parfois totalement fantaisiste et fantasmé, du voyage en Chine de Marco Polo, tel qu’il l’a relaté au poète toscan Rusticien de Pise. Le livre a marqué les esprits, mais il trahit aussi la connaissance extrêmement parcellaire et souvent erronée que l’on peut avoir encore aujourd’hui de l’Empire du Milieu.

Ce hiatus est du reste la première expérience d’un visiteur qui y met les pieds : « La Chine, affirme Tristan Murail, on ne connaît pas. Ou alors seulement par des clichés occidentalisés. Tout y est bien différent de ce que l’on imagine : l’architecture, la gastronomie – et bien sûr la musique. Voilà presque dix ans que je suis professeur invité au Conservatoire de Shanghai, et j’ai eu la surprise d’y constater la permanence des traditions, y compris musicales, qui sont pour certaines plurimillénaires. Les chinois vont jusqu’à développer des versions « modernisées » de leurs instruments traditionnels. J’ai ainsi pu entendre un sheng, cet orgue à bouche constitué d’un faisceau de tuyaux de bambou, accordé non pas sur le mode pentatonique traditionnel, mais de manière chromatique, ce qui permet potentiellement de jouer de la musique atonale. »

Ce hiatus est du reste la première expérience d’un visiteur qui y met les pieds : « La Chine, affirme Tristan Murail, on ne connaît pas. Ou alors seulement par des clichés occidentalisés. Tout y est bien différent de ce que l’on imagine : l’architecture, la gastronomie – et bien sûr la musique. Voilà presque dix ans que je suis professeur invité au Conservatoire de Shanghai, et j’ai eu la surprise d’y constater la permanence des traditions, y compris musicales, qui sont pour certaines plurimillénaires. Les chinois vont jusqu’à développer des versions « modernisées » de leurs instruments traditionnels. J’ai ainsi pu entendre un sheng, cet orgue à bouche constitué d’un faisceau de tuyaux de bambou, accordé non pas sur le mode pentatonique traditionnel, mais de manière chromatique, ce qui permet potentiellement de jouer de la musique atonale. »

C’est ainsi que naît l’idée d’une commande : le conservatoire de Shanghai lui propose de composer une pièce pour ces instruments traditionnels, adaptés ou non. Au départ, l’ambition est même de constituer un véritable orchestre symphonique d’instruments chinois – ce qui s’avère compliqué, l’instrumentarium chinois manquant notamment de graves – avant d’aboutir à l’idée d’une pièce pour guzheng (instrument à cordes pincées de la famille des cithares sur table), ensemble de 19 cordes et électronique. Pour autant, Tristan Murail ne se ferme pas à l’éventualité, par la suite, de réaliser un arrangement pour des instruments à cordes chinois, à l’instar de l’erhu (violon chinois, qui n’a que deux cordes et se joue comme une viole de gambe, à la différence que l’archet passe entre les cordes et la table).

S’il a jeté son dévolu sur le guzheng, c’est bien sûr pour son histoire immémoriale – remontant au IIIe siècle avant notre ère, le guzheng serait l’ancêtre commun à une multitude d’instruments similaires qui ont essaimé l’Est asiatique : đàn tranh vietnamien, koto japonais, gayageum coréen, yatga mongol, kacapi soundanais, jetygen kazakh –, mais aussi pour l’immense virtuosité instrumentale qui s’est développée au long de ces 24 siècles. Produisant principalement le son avec la main droite, l’interprète a en effet à la disposition de sa main gauche une large palette de modes de jeu appliqués à la partie gauche de la corde, en amont du chevalet : altérations, glissandos, vibratos contrôlés au millimètre… Dernier détail qui a pesé dans la balance : chacune des 21 cordes de l’instrument reposant sur un chevalet mobile, on peut les accorder une par une, soit autant de hauteurs que le compositeur répartit à sa guise.

Outre le cadre sonore de la pièce, Le Livre des merveilles fournit également un cadre formel : « Le récit de Marco Polo est fait d’une multitude d’histoires, plus ou moins longues, dont certaines sont manifestement fictives, dit Tristan Murail. Partant de là, la pièce est comme un livre d’images que l’on feuilletterait – s’arrêtant parfois sur quelques images ou anecdotes, tour à tour particulièrement terrifiantes ou jolies, inquiétantes ou richement décorées. »

Ainsi décrit, le dispositif peut faire penser aux Tableaux d’une exposition, mais les fragments sont ici beaucoup moins développés que chez Moussorgski, certaines miniatures durant à peine quelques secondes. Chacune d’elle a toutefois un caractère propre, « la difficulté étant de parvenir à dégager une forme de continuité de cette succession. S’il n’est pas un instrument soliste au sens d’une forme concertante, le guzheng aide à ce sentiment de cohérence formelle, incarnant musicalement le lecteur/visiteur, qui pourrait être Marco Polo ou moi, dans sa promenade d’un tableau à l’autre. »

Accorder les sons de l’intérieur - Enjeux technologiques

« Comme beaucoup d’instruments à cordes fixes, même si l’on peut changer sa hauteur en déplaçant le chevalet ou en exerçant une pression sur la partie non vibrante de la corde, le véritable problème du guzheng, c’est que son champ harmonique est fixé une fois pour toute, note Tristan Murail. Sauf si on recourt à l’informatique musicale. Harmonizer, modulation en anneau… les solutions sont alors multiples, à la fois pour transformer le son produit par le soliste en temps réel, mais aussi pour synthétiser d’autres sons, totalement étrangers au champ harmonique de l’instrument tel qu’il est joué sur scène. Cela fait plus de deux ans que, accompagné de Serge Lemouton, je fais des expériences sur un guzheng que l’Ircam a mis à ma disposition. C’est souvent ainsi que je procède pour mes pièces avec électronique : dans un premier temps, je fais quelques essais pour voir si ce que j’ai en tête est réalisable. Après quoi je compose la pièce avec tous ces sons électroniques bien présents à l’esprit, mais pas encore finalisés. Ce n’est qu’ensuite que les sons de synthèse et les transformations sont affinés. »

« Comme beaucoup d’instruments à cordes fixes, même si l’on peut changer sa hauteur en déplaçant le chevalet ou en exerçant une pression sur la partie non vibrante de la corde, le véritable problème du guzheng, c’est que son champ harmonique est fixé une fois pour toute, note Tristan Murail. Sauf si on recourt à l’informatique musicale. Harmonizer, modulation en anneau… les solutions sont alors multiples, à la fois pour transformer le son produit par le soliste en temps réel, mais aussi pour synthétiser d’autres sons, totalement étrangers au champ harmonique de l’instrument tel qu’il est joué sur scène. Cela fait plus de deux ans que, accompagné de Serge Lemouton, je fais des expériences sur un guzheng que l’Ircam a mis à ma disposition. C’est souvent ainsi que je procède pour mes pièces avec électronique : dans un premier temps, je fais quelques essais pour voir si ce que j’ai en tête est réalisable. Après quoi je compose la pièce avec tous ces sons électroniques bien présents à l’esprit, mais pas encore finalisés. Ce n’est qu’ensuite que les sons de synthèse et les transformations sont affinés. »

Outre le guzheng, l’électronique de la pièce est également élaborée à partir des sons d’un jeu de cloches chinoises en bronze : « Ce jeu, qui date du IIe siècle avant notre ère, est conservé au musée de la ville désormais tristement célèbre de Wuhan, précise Tristan Murail. Il n’est évidemment pas question de déplacer cette vingtaine de cloches anciennes – on n’a même pas eu l’autorisation de les enregistrer. Mais il se trouve que le musée de Shanghai en conserve une copie, que j’ai pu faire échantillonner par une musicologue du conservatoire. »

« Je n’utilise toutefois pas le son originel des cloches – utiliser un jeu d’échantillons préenregistrés pose le risque d’effets de redondances. En revanche, en analysant tous ces sons, j’essaie de recréer ceux des cloches, dans toute leur richesse. Je peux également en créer d’autres, plus graves ou plus aigus que les existants, ou encore rallonger ou raccourcir la résonance, ajouter de nouveaux partiels ou déplacer des partiels en fréquence… Depuis L’esprit des dunes, que j’ai réalisée à l’Ircam en 1993-1994, j’ai développé des techniques qui me permettent d’accorder les sons de l’intérieur. Au lieu de créer des harmonies par superposition de sons, je les ménage à l’intérieur même du son. Poussées plus loin, ces techniques permettent de défaire un son de cloche de son identité sonore – en faisant l’impasse sur certains éléments clés du profil dynamique de la cloche (une attaque franche et brutale, suivie d’une décrue logarithmique, avec des transitoires d’attaque très importants) – pour ne garder que la couleur de la résonance et rester dans l’harmonie pure. »

Pour tout ce travail d’alchimiste du son, Tristan Murail utilise principalement le logiciel OpenMusic, qu’il qualifie de « quartier général du compositeur ». Cependant, les programmes imaginés voilà trente ans pour L’esprit des dunes ne fonctionnent plus dans les nouveaux environnements informatiques. Il faut donc les recréer, et les ajuster pour obtenir le résultat voulu. « Pour cette pièce, se rappelle le compositeur, j’utilisais une méthode de synthèse sonore en temps réel, à l’aide de quarante oscillateurs mis ensemble (c’était la limite des ordinateurs de l’époque), avec un suivi de partiel du tout début à la toute fin du son. L’outil que j’utilisais à l’époque est obsolète. Aujourd’hui, le logiciel Partiel est censé faire la même chose, il faudra que je l’essaie. »

![]()

Photo : Tristan Murail en studio à l'Ircam © Elisabeth Schneider

Écouter : Tristan Murail

- L'esprit des dunes de Tristan Murail, 1994 (enregistré à l'Ircam, 2014)

- Désintégrations de Tristan Murail (enregistré au Centre Pompidou, 1993)

- Le fou à pattes bleues de Tristan Murail, 1990 (enregistré à l'Ircam, 1998)

- Cloches d'adieu, et un sourire... de Tristan Murail, 1992 (enregistré au Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, 2003)

- Serendib de Tristan Murail, 1991 (enregistré au Centre Pompidou, 1993)