Musique et Maladie [2/2]

Les 19 et 20 octobre prochains se tiendra à l’Ircam un colloque assorti d’un concert sur le thème « Musique et Maladie ». Imaginé et organisé par les musicologues Laurent Feneyrou et Céline Frigau Manning, ainsi que par l’historien de la médecine Vincent Barras, l’événement fera exactement ce qu’annonce son titre : éclairer mutuellement deux disciplines dont les intrications sont plus nombreuses et complexes que ce qui veut bien se dévoiler au premier coup d’œil.

Laurent Feneyrou nous en présente les grands enjeux en même temps que leurs traductions musicales que l’on pourra entendre au fil d’un programme musical défendu par l’Instant Donné le 19 octobre.

Suite et fin de cet entretien [lire la première partie].

Vous mettez de côté l’aspect cathartique (ou thérapeutique) de la musique, notamment par le musicien lui-même : pourquoi ?

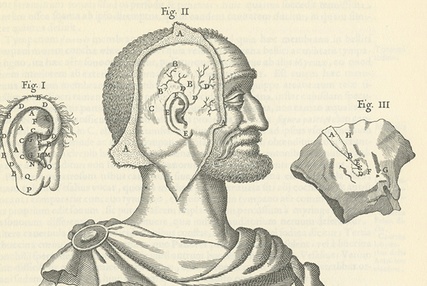

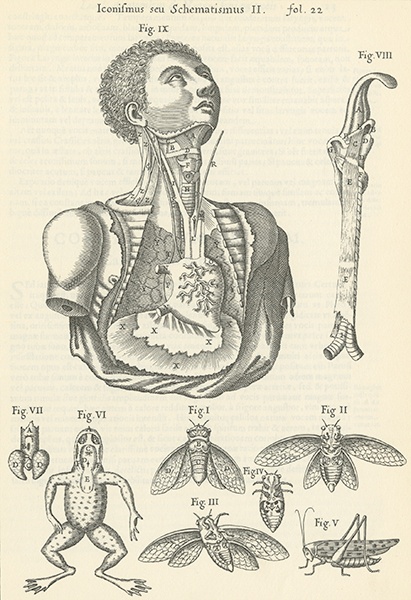

Vous avez absolument raison, et notre propos est délibéré. Nous avons écarté une vision positive de la musique, ou sa réduction au rang de pharmakon, laquelle a déjà été étudiée à travers l’histoire, et principalement avant la période que nous avons retenue – de la mort de Bach ou de Haendel à nos jours. Il ne serait pas vain de relire La République de Platon ou Les Politiques d’Aristote, où la musique, comme le sommeil et l’ivresse, et à la condition de choisir l’instrument adéquat, procure délassement, soulagement et plaisir, sert à la purification et à l’éducation, et a rapport avec la vertu dans la mesure où elle induit une certaine qualité du caractère. Bien plus, depuis Hippocrate, nombre de traités de médecine établissent ce qu’il convient d’écouter lors de la grossesse, d’une petite enfance incontinente ou agitée, de l’alimentation et de la digestion (la communication de Ryan Weber en prolongera le discours par rapport aux troubles nerveux), du bain, de la saignée ou du rapport sexuel, en vue de trouver le sommeil, ou encore à l’hôpital.  Et ils abordent la musique comme soulagement de la maladie, remède contre elle, ou comme soutien de la thérapie : contre la peste, la gale, la suette, la syphilis, la goutte, la sciatique, les maladies spasmodiques, les maux de tête, les troubles cardiaques, la stupor mentis, la litargia, l’apoplexie, la catalepsie et la consomption, l’épilepsie et les convulsions… – la liste des maladies n’est certes pas exhaustive. Ou contre les morsures d’animaux, la rage ou le tarentulisme. Athanasius Kircher y revient dans sa Musurgia Universalis, comptant que la musique peut aussi avoir pour effet, par résonance sympathique, de chasser du corps un poison. Bien sûr, la liste des maladies se modifie au cours des siècles et selon les auteurs, en raison de leurs principes médicaux et philosophiques, de même que se modifient les souvent sommaires mentions musicales. De manière polémique, je dirais que le well-being en est une déclinaison, qui a, indéniablement, un projet thérapeutique, mais aussi des prémisses socio-politiques et économiques, dès lors que le corps sain est également un outil de production. À rebours, nous recentrons le propos sur la musique, ou le musical, et nous nous demanderons comment le musicien de l’époque moderne devient un objet d’étude, un patient ou un malade de choix. Son corps doit être alors interrogé, pour reprendre les mots d’Alain Corbin, dans « la tension instaurée entre l’objet de science, de travail, le corps productif, le corps expérimental, et le corps fantasmé ». Et nous partons de la conviction que cette question doit être prise au sérieux et non pas demeurer au rang d’une curiosité historique, ou comme un chapitre secondaire, alimenté par les seuls médecins attachés à « humaniser » les sciences médicales en prônant l’apport des arts, dont la qualité principale serait de développer la sensibilité, l’empathie ou la compréhension universelle ; en somme, qu’il y a bien là, aux frontières de l’histoire de la musique, du corps et de la médecine, un vaste champ de recherches pour les musicologues, historiens de la médecine et philosophes des sciences, à parts égales.

Et ils abordent la musique comme soulagement de la maladie, remède contre elle, ou comme soutien de la thérapie : contre la peste, la gale, la suette, la syphilis, la goutte, la sciatique, les maladies spasmodiques, les maux de tête, les troubles cardiaques, la stupor mentis, la litargia, l’apoplexie, la catalepsie et la consomption, l’épilepsie et les convulsions… – la liste des maladies n’est certes pas exhaustive. Ou contre les morsures d’animaux, la rage ou le tarentulisme. Athanasius Kircher y revient dans sa Musurgia Universalis, comptant que la musique peut aussi avoir pour effet, par résonance sympathique, de chasser du corps un poison. Bien sûr, la liste des maladies se modifie au cours des siècles et selon les auteurs, en raison de leurs principes médicaux et philosophiques, de même que se modifient les souvent sommaires mentions musicales. De manière polémique, je dirais que le well-being en est une déclinaison, qui a, indéniablement, un projet thérapeutique, mais aussi des prémisses socio-politiques et économiques, dès lors que le corps sain est également un outil de production. À rebours, nous recentrons le propos sur la musique, ou le musical, et nous nous demanderons comment le musicien de l’époque moderne devient un objet d’étude, un patient ou un malade de choix. Son corps doit être alors interrogé, pour reprendre les mots d’Alain Corbin, dans « la tension instaurée entre l’objet de science, de travail, le corps productif, le corps expérimental, et le corps fantasmé ». Et nous partons de la conviction que cette question doit être prise au sérieux et non pas demeurer au rang d’une curiosité historique, ou comme un chapitre secondaire, alimenté par les seuls médecins attachés à « humaniser » les sciences médicales en prônant l’apport des arts, dont la qualité principale serait de développer la sensibilité, l’empathie ou la compréhension universelle ; en somme, qu’il y a bien là, aux frontières de l’histoire de la musique, du corps et de la médecine, un vaste champ de recherches pour les musicologues, historiens de la médecine et philosophes des sciences, à parts égales.

Image : Athanasius Kircher, Musurgia universalis sive ars magna consoni et dissoni, Rome, Ex typographia Haeredum Francesci Corbellitti, 1650, vol. 1, vis-à-vis de la page 22.

Une dernière observation : on trouve dans certains textes médicaux historiques l’idée que la musique prolongerait la vie. Or, en choisissant la maladie, nous insistons sur le chaînon manquant de ce que Michel Foucault appelait dans Naissance de la clinique une « trinité technique et conceptuelle » : vie, maladie et mort en laquelle culmine le triangle, que l’expérience médicale intègre à sa science et à ses institutions, mais que le monde de la civilisation moderne, avec zèle jusqu’à l’excès, relègue dans les marges de la vie publique.

Vous le mentionniez vous-même un peu plus tôt, en évoquant les divers actes de travail du colloque : s’agissant de musique et de maladie, l’une des premières pensées qui vient est la santé mentale – que l’on songe aux hallucinations auditives, par exemple, et plus largement aux liens étroits entre folie et créativité. À cet égard, les interventions dans le cadre du colloque, mais aussi certaines œuvres au programme, soulignent l’évolution historique de la frontière intangible qui sépare la norme du hors norme : d’abord frontière entre illumination, extase mystique, et créativité, elle glisse graduellement vers une vision plus médicale, celle d’une frontière entre pathologie mentale et créativité – vision qui qualifie différemment l’état, mais sans en changer les effets.

Oui. Le cas le plus fameux est, bien sûr, celui de Schumann, que nous n’aborderons pas lors du colloque, de ses acouphènes lancinants et de ses perceptions auditives étranges, avec démangeaisons diffuses, dont le musicien s’ouvrit à Mendelssohn. Ces hallucinations auditives se maintiendront, douloureusement, au cours des dernières années : une note fixe, un la constant, pendant la nuit, puis le jour entier, des phrases musicales complexes, à l’occasion orchestrées, une œuvre symphonique ou la dictée d’un thème merveilleusement mélodieux.

Nous aborderons la maladie mentale selon plusieurs perspectives : Jean-François Lattarico sur la représentation de l’asile psychiatrique dans l’Agnese de Buonavoglia et Paër ; Andriana Soulele sur la mise en musique d’écrits d’aliénés dans Mots bruts d’Alexandros Markeas, Annelies Andries et Marie Louise Herzfeld-Schild sur la mélancolie au début du XIXe siècle, Jon Fessenden sur l’autisme musical, Pierre Brouillet et Mathias Winter sur l’« oreille des idiots », Jean-Christophe Coffin sur Lombroso et la pathologisation du génie musical italien, indépendamment de la programmation, après le concert, d’Une page folle, film de Teinosuke Kinugasa avec une musique de Mayu Hirano, qui porte aussi sur la représentation de l’asile.

C’est une question qui traverse pareillement Infinito nero de Salvatore Sciarrino, sur des textes de Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi, et qui sera interprété par L’Instant Donné lors du concert du 19 octobre. À la suite d’une maladie non diagnostiquée et qui la mena à l’article de la mort, cette jeune professe connut quarante jours d’extases, dont Sciarrino s’inspire du modèle extrême d’oralité, en excès et en défaut. On relate que huit novices entouraient la sainte : quatre répétaient ses propos, dits trop vite, scandés, en cascade, jaillissant comme d’une mitraillette, avant qu’elle ne sombre, épuisée, dans un silence profond et une jouissance indicible ; quatre autres transcrivaient ce qui leur était répété. C’est encore de vérité religieuse, d’approche spirituelle du délire, qu’il est question, avant que Charcot et Janet n’exercent leur science médicale et que la psychiatrie moderne ne voie dans ces agitations convulsives ou la rigidité de certains membres les symptômes d’une maladie. Sciarrino se tient à cette intersection, entre, d’une part, la religion et le verbe de la Renaissance tardive, et, d’autre part, une certaine psychologie du mystique, dans le regard et l’iconographie de la Salpêtrière, les mouvements de l’extatique à terre et les tensions de son corps comme un arc soutenu par les pieds et les épaules.

C’est une question qui traverse pareillement Infinito nero de Salvatore Sciarrino, sur des textes de Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi, et qui sera interprété par L’Instant Donné lors du concert du 19 octobre. À la suite d’une maladie non diagnostiquée et qui la mena à l’article de la mort, cette jeune professe connut quarante jours d’extases, dont Sciarrino s’inspire du modèle extrême d’oralité, en excès et en défaut. On relate que huit novices entouraient la sainte : quatre répétaient ses propos, dits trop vite, scandés, en cascade, jaillissant comme d’une mitraillette, avant qu’elle ne sombre, épuisée, dans un silence profond et une jouissance indicible ; quatre autres transcrivaient ce qui leur était répété. C’est encore de vérité religieuse, d’approche spirituelle du délire, qu’il est question, avant que Charcot et Janet n’exercent leur science médicale et que la psychiatrie moderne ne voie dans ces agitations convulsives ou la rigidité de certains membres les symptômes d’une maladie. Sciarrino se tient à cette intersection, entre, d’une part, la religion et le verbe de la Renaissance tardive, et, d’autre part, une certaine psychologie du mystique, dans le regard et l’iconographie de la Salpêtrière, les mouvements de l’extatique à terre et les tensions de son corps comme un arc soutenu par les pieds et les épaules.

Image : Désiré-Magloire Bourneville et Paul Regnard, Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière, vol. 2, Attitudes passionnelles : Extase (planche XXIII), Paris, Progrès médical / Adrien Delahaye, 1878.

J’aborderai cette œuvre, ainsi que deux autres « folies religieuses », mettant en scène, par des hommes, des femmes psychotiques, névrotiques ou perverses, un male gaze nous invitant à une théorie du genre, dans une forme, lyrique, où ce genre s’exprime volontiers avec emphase : Les Diables de Loudun de Penderecki et les Exercices du silence de Brice Pauset, qui compose l’historicisation de la pathologie : après les cris et la « possession », viennent la négation, l’abandon de soi, l’extase de Louise du Néant, mystique du Grand Siècle, qui avait aimé la chair et en scrute désormais la décomposition, tournant autour des ulcères, des varices ouvertes et des peaux vérolées, sur lesquelles elle appose ses lèvres ; l’abondante littérature psychologique de la fin du XIXe siècle et de la première moitié du XXe siècle sur ce type de cas (L’Expérience religieuse, essai de psychologie descriptive de William James, De l’angoisse à l’extase de Pierre Janet, Le Surnaturel et les dieux d’après les maladies mentales, essai de théogénie pathologique de Georges Dumas…, dont Pauset s’inspire des descriptions cliniques pour ses gestes vocaux et instrumentaux) ; l’expérience contemporaine, enfin, d’une « schize » de l’espace musical et, donc, de la désorientation sensorielle, qui dénote, elle, d’autres détenus.

Le simple cas de la surdité devrait nous interpeller : vous êtes-vous intéressés à ce que disent les chercheurs en médecine ou en neuroscience des liens entre musique et surdité ?

Non, par faute d’intervenant sur ce thème, mais la question est fondamentale – y compris chez certains maîtres contemporains. Cependant, si nous l’avions abordée, cela aurait été dans une perspective non neuroscientifique, mais historique, scrutant les regards successifs. Par exemple, pour citer l’exemple le plus attendu, celui de Beethoven, sa surdité est attribuée à plusieurs causes depuis presque deux siècles : typhus, au sens de l’époque, méningite, syphilis méningo-vasculaire, syphilis congénitale, insuffisance ou atteinte vasculaire, otospongiose, otosclérose cochlaire, ostéite déformante, avec remaniement du tissu osseux, intoxication iatrogène au mercure ou au plomb, maladie auto-immune neurosensorielle, syndrome de Cogan… – sans même évoquer les conséquences des bombardements de Vienne, en 1809, sur son audition. La syphilis, non attestée par l’autopsie, est retenue sur la base de données biographiques, parmi lesquelles sa commande, en 1819, de l’Exposé des symptômes de la maladie vénérienne de Louis-Vivant Lagneau, à peine traduit en allemand, et une lettre du 19 juin 1817 à la comtesse Anna Marie Erdödy, dans laquelle Beethoven fait allusion à un traitement à base de mercure, que l’on utilisait pour la syphilis, mais aussi pour des affections rhumatismales ou cutanées.

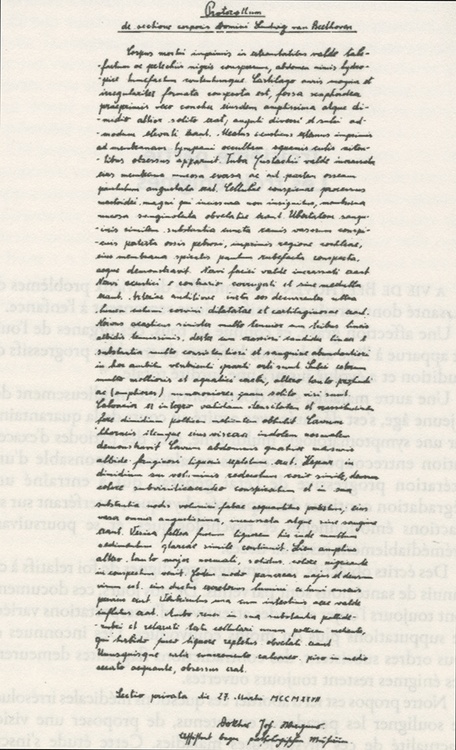

Nous aurions aussi étudié le rapport d’autopsie, ses présupposés, médicaux, sur l’art et sur l’artiste, ses méthodes, l’histoire des médecins qui l’ont pratiquée, ce que le texte révèle de leur manière d’appréhender le corps du musicien… « Le cartilage du pavillon de l’oreille est de grande taille et de forme irrégulière : la fossette naviculaire, en particulier, est agrandie ; la conque est très grande et moitié plus profonde que d’habitude ; les branches de l’anthélix sont très divergentes et les replis sont très profonds. Le conduit auditif externe est rempli de squames cutanées brillantes jusqu’à la membrane tympanique, qui s’en trouve masquée. La trompe d’Eustache est considérablement épaissie. Le protympanum est un peu étroit. L’apophyse mastoïde est de grande taille, mais sans particularités en ce qui concerne les sutures osseuses. Les cellules apparaissent tapissées d’une muqueuse teintée de sang. L’ensemble de la partie pétreuse du temporal est parcouru par un réseau vasculaire visible et présente également une grande quantité de substance évoquant du sang, en particulier dans la région de la cochlée, dont la membrane spirale apparaît un peu rougie. Les nerfs faciaux sont très épais. Les nerfs acoustiques, par contre, sont plissés et dépourvus de myéline. Les artères auditives y afférentes sont dilatées au-delà de la taille d’un tuyau de plume de corbeau (quatre à cinq fois le calibre normal) et leur consistance est cartilagineuse. Le nerf acoustique gauche est de loin le plus fin et présente trois racines blanchâtres et très ténues ; le nerf droit présente une racine blanche et beaucoup plus grosse. » Longtemps tenu pour perdu, ce document, rédigé en latin, daté du 27 mars 1827, et signé Johann Wagner (assistant du Musée de pathologie de Vienne qui, avec Carl von Rokitansky, bientôt éminent représentant de l’anatomie pathologique moderne, pratiqua l’autopsie), a été retrouvé en 1970 seulement, à l’Institut d’anatomie pathologique de l’Université de Vienne – il faudra attendre 2006 pour la publication du rapport d’autopsie de Schumann et du dossier médical de ses années à la clinique d’Endenich. L’importance de ces textes, pour la connaissance des musiciens et l’histoire de la musique, me paraît incontestable.

Nous aurions aussi étudié le rapport d’autopsie, ses présupposés, médicaux, sur l’art et sur l’artiste, ses méthodes, l’histoire des médecins qui l’ont pratiquée, ce que le texte révèle de leur manière d’appréhender le corps du musicien… « Le cartilage du pavillon de l’oreille est de grande taille et de forme irrégulière : la fossette naviculaire, en particulier, est agrandie ; la conque est très grande et moitié plus profonde que d’habitude ; les branches de l’anthélix sont très divergentes et les replis sont très profonds. Le conduit auditif externe est rempli de squames cutanées brillantes jusqu’à la membrane tympanique, qui s’en trouve masquée. La trompe d’Eustache est considérablement épaissie. Le protympanum est un peu étroit. L’apophyse mastoïde est de grande taille, mais sans particularités en ce qui concerne les sutures osseuses. Les cellules apparaissent tapissées d’une muqueuse teintée de sang. L’ensemble de la partie pétreuse du temporal est parcouru par un réseau vasculaire visible et présente également une grande quantité de substance évoquant du sang, en particulier dans la région de la cochlée, dont la membrane spirale apparaît un peu rougie. Les nerfs faciaux sont très épais. Les nerfs acoustiques, par contre, sont plissés et dépourvus de myéline. Les artères auditives y afférentes sont dilatées au-delà de la taille d’un tuyau de plume de corbeau (quatre à cinq fois le calibre normal) et leur consistance est cartilagineuse. Le nerf acoustique gauche est de loin le plus fin et présente trois racines blanchâtres et très ténues ; le nerf droit présente une racine blanche et beaucoup plus grosse. » Longtemps tenu pour perdu, ce document, rédigé en latin, daté du 27 mars 1827, et signé Johann Wagner (assistant du Musée de pathologie de Vienne qui, avec Carl von Rokitansky, bientôt éminent représentant de l’anatomie pathologique moderne, pratiqua l’autopsie), a été retrouvé en 1970 seulement, à l’Institut d’anatomie pathologique de l’Université de Vienne – il faudra attendre 2006 pour la publication du rapport d’autopsie de Schumann et du dossier médical de ses années à la clinique d’Endenich. L’importance de ces textes, pour la connaissance des musiciens et l’histoire de la musique, me paraît incontestable.

Image : Johann Wagner, Manuscrit du rapport d’autopsie de Ludwig van Beethoven, 1827, conservé au Pathologisch-Anatomischen Bundesmuseum de Vienne.

La créativité – et son produit : l’œuvre – est-elle vue dans certaines œuvres au programme comme un symptôme de la maladie (on pense à Etwas ruhiger im Ausdruck de Donatoni par exemple) ?

C’est le point le plus délicat. Quelle est la part de la pathologie et celle de l’invention musicale ? Dans le cas de Donatoni, la question est médicalement double : le diabète jusqu’au coma, d’une part, résultant de conduites alimentaires délétères, auquel nous avons fait allusion et qu’Emile Wennekes étudiera dans Alfred, Alfred, avec d’autres représentations de cette maladie (Diagnosis: Diabetes de Michael Park et La straordinaria vita di Sugar Blood d’Alberto García Demestres) ; une structure bipolaire, d’autre part, qui ne relève pas d’une banale psychologie, mais d’une structure existentielle, marquée par l’absence de volition : « La volonté était quelque chose d’essentiel dont j’étais totalement exclu. » De volonté, Donatoni n’avait donc pas. Dès lors, il lui fallait non la cacher, l’occulter ou la réprimer, mais constater son manque, qui met en doute l’existence propre et en transforme les modalités : le moi ne pense pas, mais est pensé, n’agit pas, mais est agi, comme Donatoni le disait volontiers. Ainsi, la question du Soi est à vif. On pourra considérer que la négation, l’ironie, le sarcasme, le doute, le pathos de la dépendance, la conscience des illusions de l’art, la mortification de soi dans l’œuvre, autant d’ailleurs que de l’œuvre, l’expiation de la subjectivité en sont la manifestation, aucunement littéraire. Etwas ruhiger im Ausdruck sollicite une succession de points de « maintenant » comme incapables de se maintenir et de s’anticiper, sans continuité ni ancrage. Voilà qui constitue l’essence de la distension temporelle maniaque. Le psychiatre Ludwig Binswanger utilisait à cet égard le terme Momentanisierung, momentanéisation ou mise-en-moments.

Autrement dit, nous saisissons la menace d’un présent nu, sans avant ni après, dans un presto privé ou presque des valeurs de la mémoire et de l’attente. Rien ne s’écoule ni n’advient, rien ne dure. De même, l’espace se restreint : tout y paraît sous la main, sans distance, dans une proximité où l’on se saisit de tout et de tous. Dans cet espace, auquel il s’adosse et qu’il embrasse, le maniaque, à la surface de son propre fond, s’esquive et se dissimule à soi. Son tourment est la défaillance d’un désir marqué du désir de l’Autre – du fait de son absence de volition. Il est l’être anonyme, dans l’inauthenticité du On, non vers l’autre, mais vers une expérience de l’altérité où l’alter ego devient neutre, aliud, et où autrui se réduit à l’alienus, à l’outil, à l’objet utilisé et consommé, comme les trois premiers temps de la huitième mesure de la deuxième des Cinq Pièces pour piano op. 23 que Etwas ruhiger im Ausdruck emprunte à Schoenberg, un matériau soumis ensuite aux automatismes de la combinatoire. Le maniement des mots ou des sons jusqu’à la chosification, ce que l’œuvre théorique et musicale de Donatoni magnifie, implique une autre modalité de l’énonciation. Est-ce pour autant un jeu de langage substituant aux usages communs l’association volatile et la précipitation ? Le tourbillon, le vortex de sons, traduit-il ivresse, bondissement et luminosité maniaques ? S’agit-il de l’expression symptomatique d’une maladie ou, davantage, de sa représentation ? Ou de la représentation de sa représentation ?

Propos recueillis par Jérémie Szpirglas