Musique et Maladie [1/2]

Les 19 et 20 octobre prochains se tiendra à l’Ircam un colloque assorti d’un concert sur le thème « Musique et Maladie ». Imaginé et organisé par les musicologues Laurent Feneyrou et Céline Frigau Manning, ainsi que par l’historien de la médecine Vincent Barras, l’événement fera exactement ce qu’annonce son titre : éclairer mutuellement deux disciplines dont les intrications sont plus nombreuses et complexes que ce qui veut bien se dévoiler au premier coup d’œil.

Laurent Feneyrou nous en présente les grands enjeux en même temps que leurs traductions musicales que l’on pourra entendre au fil d’un programme musical défendu par l’Instant Donné le 19 octobre.

D’abord et avant tout, comment est née l’idée de ce colloque/concert « Musique et Maladie » ?

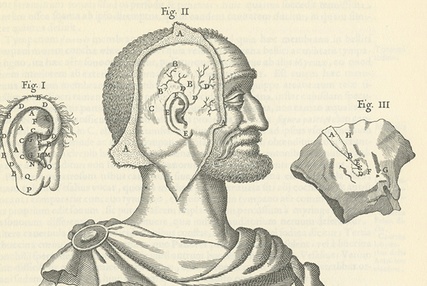

L’idée, ancienne, remonte à 2015. Le musicologue Gianfranco Vinay avait attiré mon attention sur un essai de son collègue, Giovanni Morelli (1942-2011). Cet essai, intitulé « Musique et maladie », avait paru, en italien, dans l’Enciclopedia della musica dirigée par Jean-Jacques Nattiez, mais n’avait pas été traduit dans l’édition française, ce que je me décidai alors à faire. Peintre, dessinateur, écrivain, poète, performer, cinéphile, et surtout médecin de formation, Morelli enseigna d’abord l’anatomie à l’Académie des beaux-arts de Bologne, puis la musicologie à l’université Ca’ Foscari de Venise, avant de créer l’Institut pour la musique de la Fondation Cini, qu’il dirigea jusqu’à sa mort. Dans son essai, extraordinaire d’érudition et de virtuosité conceptuelle et d’écriture, Morelli esquisse quantité de thèmes de recherche : sur la manière hygiénique, sédative, sinon narcotique, et morale, dont la médecine considère la  musique de l’Antiquité à l’âge classique (musique et médecine) ; sur la transition, à l’époque baroque, vers un nouvel ordre dans lequel le patient se découvre lui-même sujet, ouvrant les voies du XIXe siècle, où l’artiste s’expose malade, de plus en plus gravement, et où le regard médical cherche, dans chaque symptôme, et jusque dans les autopsies (de Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin…), la marque du génie (musiciens et maladies) ; sur un nouveau changement d’ère, avec l’avènement de la modernité, où la maladie n’est plus une déviation de la norme, mais une composition, par le corps, d’un autre mode de vivre, quand une médecine technique tend à étudier la maladie sans le malade, à la déshumaniser, à la « désubjectiver », à l’heure des analyses, radiographies, scanners ou IRMs, du cancer, du sida et autres épidémies d’aujourd’hui (musiques et maladies).

musique de l’Antiquité à l’âge classique (musique et médecine) ; sur la transition, à l’époque baroque, vers un nouvel ordre dans lequel le patient se découvre lui-même sujet, ouvrant les voies du XIXe siècle, où l’artiste s’expose malade, de plus en plus gravement, et où le regard médical cherche, dans chaque symptôme, et jusque dans les autopsies (de Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin…), la marque du génie (musiciens et maladies) ; sur un nouveau changement d’ère, avec l’avènement de la modernité, où la maladie n’est plus une déviation de la norme, mais une composition, par le corps, d’un autre mode de vivre, quand une médecine technique tend à étudier la maladie sans le malade, à la déshumaniser, à la « désubjectiver », à l’heure des analyses, radiographies, scanners ou IRMs, du cancer, du sida et autres épidémies d’aujourd’hui (musiques et maladies).

Gravure représentant Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827). MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY / PHOTONONSTOP

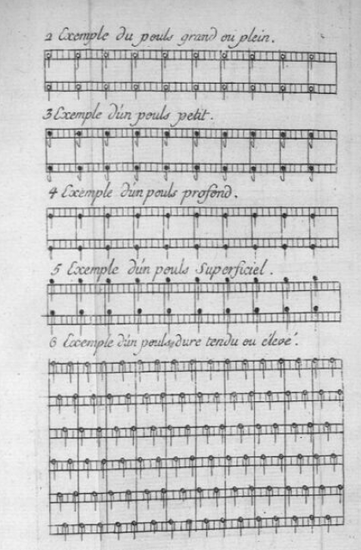

Dans les mêmes années, j’avais organisé un dialogue, qui s’est avéré d’une étonnante richesse, entre Salvatore Sciarrino et le philologue, helléniste, latiniste et historien de la médecine Jackie Pigeaud (1937-2016), autour de la mélancolie. Pigeaud nous laisse une œuvre admirable et féconde pour la musicologie, par ses ouvrages sur la « maladie de l’âme », ou sur l’art et le vivant, mais aussi, plus spécifiquement, sur musique et pouls, depuis Hérophile de Chalcédoine, inventeur, aux IVe- IIIe siècles avant Jésus-Christ, de la sphygmologie (étude du pouls),  et découvrant qu’il y a « de la régularité, du rythme dans le corps », pour citer Pigeaud, jusqu’à la Nouvelle Méthode facile et curieuse, pour connaître le pouls par les notes de la musique (1769) du médecin lorrain François Nicolas Marquet et jusqu’aux expérimentations actuelles sur le rythme cardiaque et ses troubles, relativement à la composition et à la perception de la musique. C’est dans ce contexte que s’inscrit l’exécution, lors du concert du 19 octobre, de Cardiophonie (1971) de Heinz Holliger.

et découvrant qu’il y a « de la régularité, du rythme dans le corps », pour citer Pigeaud, jusqu’à la Nouvelle Méthode facile et curieuse, pour connaître le pouls par les notes de la musique (1769) du médecin lorrain François Nicolas Marquet et jusqu’aux expérimentations actuelles sur le rythme cardiaque et ses troubles, relativement à la composition et à la perception de la musique. C’est dans ce contexte que s’inscrit l’exécution, lors du concert du 19 octobre, de Cardiophonie (1971) de Heinz Holliger.

Si la Covid, avec ses conséquences sur nos humeurs, a retardé la tenue de ce colloque, organisé avec Céline Frigau Manning, de l’université de Lyon 3, et Vincent Barras, de l’Institut des humanités en médecine (Lausanne), et avec la collaboration de Philippe Lalitte et Emmanuel Reibel, Morelli et Pigeaud en demeurent, pour ce qui me concerne, les deux figures tutélaires.

François Nicolas Marquet, Nouvelle méthode facile et curieuse pour connaître le pouls par les notes de la musique, Amsterdam, 1769, seconde édition, sans page.

Quels sont les principaux axes de recherche mis en avant au fil de ce colloque ?

Le comité scientifique a invité à des communications selon deux axes de recherches principaux :

1. Des études de cas ou des pathographies de compositeurs et d’interprètes (comme Glenn Gould, abordé par Vincent Barras), dans le but de décrire les conséquences de la maladie sur la biographie, la pratique, voire l’esthétique du musicien. La pathographie implique, contre les injonctions du structuralisme, un renouveau de la biographie et un régime singulier de discursivité. En ce sens, nous ne visons ni le pur établissement d’un diagnostic, ni une énième tentative d’interprétation médicale qui prétendrait expliquer la créativité des musiciens ou, plus largement, le phénomène artistique au prisme des savoirs médicaux du moment, mais l’examen des pathographies existantes ou le genre même dont elles relèvent, en questionnant la tentation de soustraire le regard médical à sa détermination historique, ainsi que les modalités de prise en considération, du point de vue musical comme musicologique, du corps naturel de l’artiste.

2. Des études par maladies : le diabète, le sida ou la maladie d’Alzheimer, mais aussi, dans le champ psychiatrique, la schizophrénie, les troubles bipolaires ou l’hystérie dissociative, auxquels s’ajoutent les pathologies construites comme spécifiquement musicales, comme les amusies, hypermusies, obsessions, « vers auditifs » ou « vers cérébraux ». Nous entendons observer l’histoire de ces maladies et de leurs descriptions médicales, à travers traités et documents historiques, et examiner la manière dont elles sont rapportées à des musiciens, à leurs œuvres ou à leurs interprétations, à leurs discours, ainsi qu’à des représentations musicales, notamment dans le domaine, également littéraire et scénique, de l’opéra. Comment par exemple, au-delà de La Traviata, et pour prendre une œuvre récente, Franco Donatoni représente-t-il son coma diabétique, dans Alfred, Alfred, où il tenait sur scène son propre rôle ?

Alfred, Alfred de Franco Donatoni, commande de T&M-Nanterre et du Festival Musica de Strasbourg © Droits réservés

Un troisième axe, qui me paraît riche de perspectives, mais a trouvé peu d’échos chez les musicologues, les historiens de la médecine et les philosophes des sciences, est celui des études par disciplines médicales, en mesurant, par exemple, l’histoire de l’obstétrique à l’aune de la représentation de la naissance en musique ; l’histoire de la pédiatrie à celle de l’enfance, vivace depuis le XIXe siècle, de Schumann à Stockhausen ; l’histoire de la pneumologie, particulièrement efficiente dans le cas du romantisme tardif, à celle du souffle ; ou encore l’histoire de la cardiologie à celle du rythme – ce que nous avons déjà mentionné.

Justement, quelle histoire de la santé et/ou de la médecine peut-on lire à travers celle de la musique, et vice versa ?

Il conviendrait d’étudier, relativement au thème de la folie créatrice, la syphilis, dont moururent notamment Donizetti, Chabrier et, plus emblématiquement encore, Hugo Wolf. Schubert échappa non au mercure, toxique sur le rein, et qui n’est pas sans conséquence sur l’état général du patient (lassitude, anémie chronique qui aggrave l’asthénie, perte de poids, diminution de l’appétit, goût métallique dans la bouche, nausées, vomissements, insomnies et somnolences diurnes, hypertension artérielle, parfois sévère et responsable de céphalées, de troubles visuels, d’étourdissements ou d’atteintes cardiaques…), mais au stade tertiaire de la maladie, dont l’issue fatale fut devancée par une septicémie intestinale. Quoi qu’il en soit, Bach, Haendel, Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schubert, Chopin ou Puccini permettent d’aborder la chirurgie de l’œil, des tableaux cliniques complexes, une maladie héréditaire, deux des grands maux du XIXe siècle, la syphilis, donc, et la tuberculose, ainsi que le cancer, mais aussi l’histoire de l’hygiène, de la nutrition, de la sexualité, de l’hôpital, de l’enseignement de la médecine, dont témoigna Berlioz dans ses Mémoires, de la pharmacologie (la correspondance des Mozart, Leopold et Wolfgang Amadeus, est passionnante à cet égard)… Solveig Serre et Luc Robène étudieront, plus près de nous, les conséquences des paradis artificiels et des maladies qui leur sont associées par les substances et leurs usages (sida, hépatite C, troubles psychiatriques…) sur la communauté punk.

Plutôt que de sonder les relations entre compositeur et médecin, à l’instar, pour citer deux exemples, de celles, remarquables, de Beethoven avec Malfatti ou de celles de Brahms avec Billroth, ce sont donc les maladies qui nous importent, même si les descriptions des symptômes n’impliquent pas toujours la confirmation d’un diagnostic précis. À cet égard, le genre de la pathographie demeure contesté en histoire de la médecine, le médecin de tel ou tel compositeur, qu’il soit baroque, classique, romantique ou moderne, ne regardant pas le corps de son patient comme le regarderait un médecin d’aujourd’hui : principes, grilles de lecture et cadres nosographiques se transforment constamment.

Comment, dès lors, établir un diagnostic sur des constatations faites par d’autres, qui constataient autrement ? Il est un autre risque, artistique, celui de se saisir dudit diagnostic pour le « plaquer » sur l’écriture musicale, de réduire en conséquence l’invention créatrice au symptôme. Schumann n’y échappe pas : brusquerie des changements d’humeur, bizarreries harmoniques, excentricités formelles… Ce point est valable dès la description du corps du musicien, avant même ses éventuelles pathologies : dire ce corps mesure environ 1,55 m est une chose, dire le corps de Schubert mesure 1,55 m en est une autre, et dire le corps de Schubert, mesurant 1,55 m, infère une inscription singulière dans le monde en est encore une troisième. Or, c’est, je pense, l’un de nos principes que de refuser cette troisième voie, tout autant que de ne pas établir de lien de causalité linéaire entre pathologie et œuvre. Dans son essai, Morelli faisait deux exceptions à la règle : la première, ponctuelle, chez Chopin, dont l’« extrême propension à la fatigue » pourrait avoir induit un format, voire des genres musicaux, plus courts que la sonate classique, et indépendamment des notions romantiques de miniature ou de fragment ; la seconde, essentielle, et fort partagée, chez les derniers Schubert ou Mendelssohn notamment, tiendrait à l’urgence créatrice devant la maladie, non devant tel ou tel virus, telle ou telle infection, mais face à la crainte d’une mort imminente.

Propos recueillis par Jérémie Szpirglas