Manuel Poletti – « On Air » : travailler avec Tomás Saraceno

Depuis quelques mois, le réalisateur en informatique musicale Manuel Poletti travaille avec le plasticien Tomás Saraceno pour préparer la carte blanche que lui consacre le Palais de Tokyo.

Quelles sont selon votre expérience les principales différences entre une collaboration dans le domaine de la musique et une dans le domaine des arts visuels ?

Quelles sont selon votre expérience les principales différences entre une collaboration dans le domaine de la musique et une dans le domaine des arts visuels ?

De manière générale, les pratiques de l’Ircam et, plus généralement, les pratiques qui ont cours dans le milieu du spectacle vivant, et celles du milieu des arts visuels sont aux antipodes les unes des autres. Ce sont deux cultures qui ne se connaissent pas, ou mal. En revanche, ce qui m’a frappé d’emblée en commençant ce projet, c’est que l’envie de se connaître est bien présente. C’est particulièrement vrai des équipes du Palais de Tokyo, qui ont tout de suite compris le sens de notre travail et nous ont accompagnés tout du long.

Notre première mission a été de tâcher de magnifier tout ce qui relève du sonore dans l’exposition, tant dans la mise en œuvre (et principalement la spatialisation) que dans le contenu.

Quelle est justement la place du son dans l’œuvre de Tomás Saraceno ?

Il aime le son. Celui-ci fait partie intégrante de ses créations, mais on ne peut pas réellement parler d’artiste sonore : c’est un artiste qui utilise le son. La plupart du temps, il intègre et/ou crée des sonifications de données scientifiques – notamment des données d’éléments cosmiques (mouvement de planètes, etc.). Notre rôle dans le cadre de cette production est d’être force de propositions en termes de structure, de matériau et de diffusion – sans aller jusqu’à être compositeur – afin d’enrichir l’aspect sonore qui est déjà en germe dans son travail. J’ai ainsi suggéré des modèles simples de composition. Je leur ai par exemple montré combien une combinaison de sons, quels qu’ils soient (et même des sonifications de données scientifiques), gagne à être structurée spectralement, des basses jusqu’aux aigus. En donnant une topologie spectrale (qui peut correspondre aux éléments d’un groupe de rock par exemple : basse, batterie, guitare rythmique, clavier, chant lead et chœur) aux sons utilisés dans une installation sonore, on peut l’animer de manière simple et efficace. Après, la nature de ces sons et leurs évolutions relèvent du choix de l’artiste.

L’un des grands enjeux de cette exposition est naturellement la diffusion sonore et la spatialisation – enjeux compliqués encore par l’acoustique pour le moins inadaptée du Palais de Tokyo.

Inadaptée, c’est le moins qu’on puisse dire ! Le Palais de Tokyo est un espace brut ouvert. Par conséquent, son acoustique est donc également, par nature, « brute et ouverte ». L’idée est donc de fabriquer un espace acoustique intégré à l’espace architectural.

De manière générale, chaque pièce d’importance de cette exposition comprend un aspect sonore. Ce n’est bien sûr pas une innovation : c’est même assez courant dans les arts visuels contemporains. En revanche, la spatialisation, c’est-à-dire créer un espace sonore homogène comme nous savons le faire, représente potentiellement une valeur ajoutée pour le Palais de Tokyo. Pour cela, nous procédons à de nombreuses mesures de l’acoustique : nous envoyons des sons tests pour en capter le retour acoustique et l’analyser afin de calibrer le système (equalization, delays, etc.). Lorsque tout est en place, nous pouvons traiter ces nouveaux « espaces dans l’espace » comme des salles virtuelles, grâce aux outils de spatialisation habituels qu’on utilise pendant les concerts (notamment le Spatialisateur).

Outre ce travail de spatialisation, vous intervenez plus particulièrement sur trois pièces : Webs of At-ten(t)sion, Sounding the Air et Particular Matter(s).

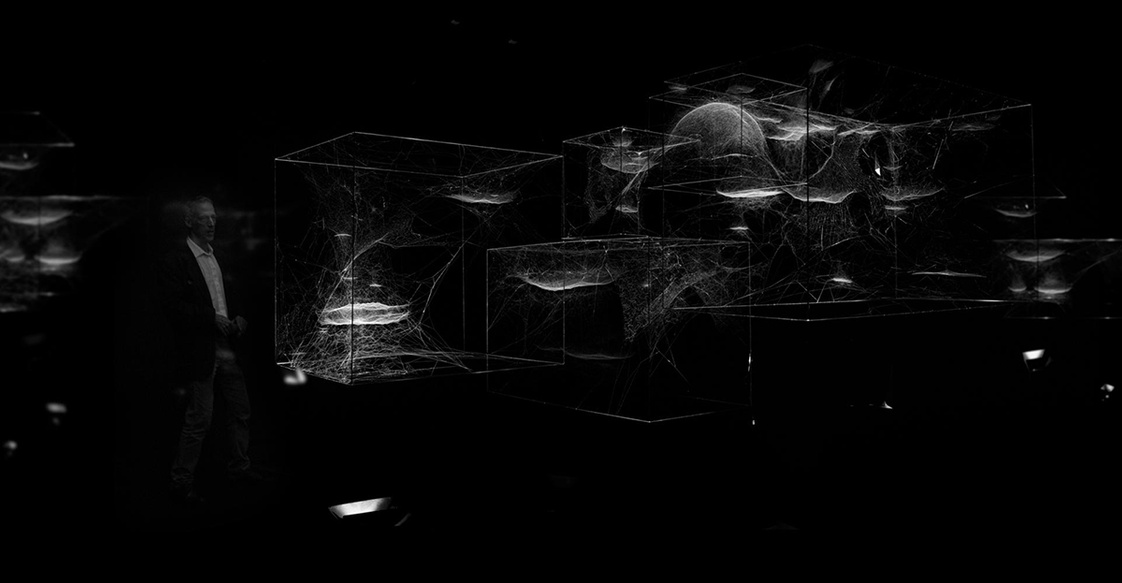

Pour chacune d’elle, nous avons exploré plusieurs pistes en collaboration avec Tomás Saraceno et son équipe. Webs of At-ten(t)sion se présente comme une constellation de milliers de fils, comme une impressionnante toile tissée, tendue dans la grande rotonde du Palais de Tokyo. Les cordes sont « sonores », c’est-à-dire que, malgré leur nature « brute » (ce ne sont pas des cordes de piano !), elles doivent produire elles-mêmes un son, amplifié, traité et diffusé – comme une harpe géante dans laquelle les visiteurs se promènent et dont ils peuvent jouer.

Webs of At-tent(s)ion. Tryout at Studio Tomas Saraceno © Photography by Studio Tomás Saraceno, 2018

L’une des pistes de réflexion a concerné la localisation de la source sonore à l’endroit où le visiteur joue. En accord avec la volonté de Tomás, qui était que les visiteurs participent à une « jam-session », j’ai aussi proposé divers scénarios afin de leur ménager un environnement propice aux interactions – un peu comme un jeu. J’ai dans ce but repris des concepts simples comme celui d’un temps lisse devenant peu à peu rythmique, ou d’un temps rythmique irrégulier évoluant vers une pulse, pour proposer aux visiteurs une partition ouverte, adaptative en temps réel, en termes d’évolutions et de potentialités, selon le nombre de visiteurs et la fréquence de leurs actions. Ces divers scénarios mènent les uns à la saturation, les autres à un appauvrissement ou carrément à l’explosion du matériau…

Pour Particular Matter(s), le travail a surtout porté, non pas sur le contenu sonore, mais sur ses qualités et sa spatialisation. La pièce se présente sous la forme d’un écran, qui diffuse une captation vidéo en temps réel de la poussière en suspension dans l’air dont les mouvements sont détectés afin de les sonifier. En même temps que cette sonification (qui passe par un synthétiseur que l’équipe de Tomás avait déjà développé en amont pour la création de l’œuvre), nous avons cherché à reproduire par la spatialisation sonore les trajectoires des grains de poussière, grâce à un plafond de haut-parleurs, afin de renforcer le lien entre visuel et sonore.

Sounding the Air est une pièce très belle à voir : ce sont cinq cordes en fil de soie d’araignées (Tomás travaille beaucoup sur les araignées) tendues sur une structure métallique de cinq ou six mètres de large. À l’instar des cordes d’une grande harpe éolienne, ces cordes oscillent en fonction des courants d’air et des flux thermiques qui animent l’atmosphère de la salle. Là encore, l’équipe de Tomás a développé une technologie de suivi des mouvements des cinq cordes, afin de les sonifier. Ce qui en sort est toutefois assez bruité, et j’ai donc proposé un design sonore. Pour rester fidèle à l’imaginaire de Tomás, qui, outre les araignées, tourne ses regards vers le cosmos, j’ai imaginé une harpe éolienne cosmique, c’est-à-dire qu’elle se comporte comme si elle réagissait à des vents cosmiques. Les sons extraits du suivi de mouvement des cordes passent donc dans des bandes filtres résonants élaborés à partir de sons d’orbites de planète (sonifiés sur un spectre harmonique classique de corde vibrante) – comme un petit système solaire sonore tournant dans l’espace au-dessus de la structure. Le suivi des mouvements des cordes d’araignées permet d’altérer légèrement les hauteurs et les volumes des filtres résonants, comme lorsqu’une corde se tend et se détend – pour rester en lien avec les cordes physiques de l’installation.

Propos recueillis par Jérémie Szpirglas, journaliste et écrivain