Biotope

De la musique pour une exposition - les enjeux formels

Habituellement, l’espace sonore d’une exposition n’est animé que par les sons émis par les œuvres et, surtout, par la rumeur du public. C’est de surcroît un lieu dans lequel on évolue. On n’y vient généralement pas pour écouter de la musique. L’oreille y est donc le sens le moins sollicité. Volontairement du moins.

« Nous sommes dans une civilisation de l’image où l’écoute de notre environnement, l’attention aux sons qui nous entourent, ne fait pas partie de nos habitudes, constate Jean-Luc Hervé. Pour inciter le public à écouter dans un environnement qui n’est pas totalement silencieux, j’ai observé ce qui se passe en milieu naturel. Au cours d’une sortie ornithologique à proximité d’une ville, même lorsqu’il y a des bruits parasites (circulation, rumeur de la ville), si l’oreille est tendue vers les chants d’oiseaux, nous n’écoutons plus le bruit de fond, attentifs aux seuls sons de type “oiseaux”, même discrets – à la recherche de la rareté sonore, de l’heureuse surprise d’un chant jamais entendu. Il s’agit donc d’intriguer le visiteur, d’éveiller sa curiosité auditive malgré le bruit de fond. L’idée est de créer un environnement sonore sur toute l’exposition, de n’être plus tout à fait dans une galerie d’exposition, de transformer le lieu par le dispositif sonore, de donner la sensation au visiteur qu’il entre dans un biotope particulier, d’où le titre de l’œuvre. »

D’autre part, dans une exposition, les durées d’écoute et le propos musical ne peuvent être de même nature que dans une situation de concert. Le public qui déambule dans la galerie d’exposition va d’une œuvre à une autre, décide lui-même de son parcours et de la durée consacrée à chaque œuvre. C’est donc lui qui impose le temps aux œuvres. « C’est l’autre contrainte forte pour l’élaboration du propos musical, qui se doit de construire des formes sonores dans la durée, dit le compositeur. C’est probablement pour cette raison que cet aspect est absent dans la plupart des installations sonores, qui préfèrent une approche plastique du son, en général associée à un objet visuel. Par ailleurs, la musique se construit à partir du silence, et il est évident qu’un matériau sonore continu ne peut fonctionner, car il devient vite lui-même un bruit de fond, au mieux une décoration, qui rejoint les autres bruits qui nous entourent et que nous n’écoutons plus. »

Là encore, le modèle de la sortie ornithologique est précieux. « Ce n’est pas un hasard si les compositeurs se sont de tout temps intéressés au chant des oiseaux. Parmi les “bruits” qui meublent notre environnement, ce sont pratiquement les seuls qui possèdent des formes temporelles complexes. Un chant d’oiseau est une forme musicale assez courte d’une durée de quelques secondes, qui se répète avec des variations. Chaque espèce est caractérisée par son chant. Mais, au sein d’une même espèce, chaque individu a ses particularités. Les individus qui occupent un même territoire se répondent les uns aux autres, créant une polyphonie où, comme dans le contrepoint, chaque voix est en relation avec les autres. Ici également, chaque agent sonore émet régulièrement de courtes séquences sonores du même type, mais variées et toujours renouvelées. Chaque individu écoute son voisin immédiat, pour inscrire son chant dans l’ensemble. Se forme ainsi une grande polyphonie où chaque agent a sa propre identité sonore, sa variabilité individuelle. Une polyphonie qui imprègne tout le bâtiment, animant l’architecture d’une présence sonore organique. »

Il faut toutefois préciser tout de suite que c’est la forme des chants d’oiseau (et plus généralement des populations animales : oiseaux, insectes ou batraciens), c’est-à-dire leur structure temporelle et polyphonique, qui sert de modèle : le matériau sonore utilisé n’imite en aucune manière les chants d’oiseaux.

Un biotope craintif - les enjeux poétiques

« La relation à la nature, de l’utilisation de modèles organiques dans la composition jusqu’à l’extension de la musique de concert dans l’environnement, est une constante dans mon travail depuis plusieurs années1 », annonce Jean-Luc Hervé. Autant dire que le thème de l’exposition, « La fabrique du vivant », lui va comme un gant. Dans Biotope, la référence au vivant se manifeste notamment dans l’occupation du lieu par des sources sonores multiples et par le comportement individuel et collectif de chacune de ces sources. Elle se manifeste également par le caractère “craintif” du dispositif : « Comme les populations de grenouilles, d’insectes ou d’oiseaux, le dispositif est sensible à la présence du public. Intrigués par les sons, les visiteurs s’approchent des points de diffusion pour mieux écouter, en chercher leur origine. Mais s’ils sont trop nombreux, ou si leurs mouvements trop brusques, ils dérangent "l’animal". Le dispositif réagit alors : l’agent sonore, à la manière d’un organisme vivant, s’affole, émet un signal d’alerte qu’il transmet à ses voisins puis se tait. Si le dérangement persiste, la panique est plus grande. L’ensemble de la population s’envole en criant et parcourt à grande vitesse les plafonds de la galerie d’exposition. Très rapidement après cette “explosion” sonore, la musique s’arrête et l’installation dans son ensemble fait silence : les "animaux" effrayés se taisent. La musique reprend lorsque le calme est revenu. »

« La relation à la nature, de l’utilisation de modèles organiques dans la composition jusqu’à l’extension de la musique de concert dans l’environnement, est une constante dans mon travail depuis plusieurs années1 », annonce Jean-Luc Hervé. Autant dire que le thème de l’exposition, « La fabrique du vivant », lui va comme un gant. Dans Biotope, la référence au vivant se manifeste notamment dans l’occupation du lieu par des sources sonores multiples et par le comportement individuel et collectif de chacune de ces sources. Elle se manifeste également par le caractère “craintif” du dispositif : « Comme les populations de grenouilles, d’insectes ou d’oiseaux, le dispositif est sensible à la présence du public. Intrigués par les sons, les visiteurs s’approchent des points de diffusion pour mieux écouter, en chercher leur origine. Mais s’ils sont trop nombreux, ou si leurs mouvements trop brusques, ils dérangent "l’animal". Le dispositif réagit alors : l’agent sonore, à la manière d’un organisme vivant, s’affole, émet un signal d’alerte qu’il transmet à ses voisins puis se tait. Si le dérangement persiste, la panique est plus grande. L’ensemble de la population s’envole en criant et parcourt à grande vitesse les plafonds de la galerie d’exposition. Très rapidement après cette “explosion” sonore, la musique s’arrête et l’installation dans son ensemble fait silence : les "animaux" effrayés se taisent. La musique reprend lorsque le calme est revenu. »

La galerie dans son ensemble devient ainsi un lieu où il faut être attentif et se faire discret pour écouter. Le visiteur tend l’oreille, son écoute s’aiguise, et il devient sensible à tous les événements qui l’entourent.

Créer un espace sonore organique - les enjeux technologiques

Prenant le contre-pied de certaines tendances actuelles dans la musique contemporaine, qui consistent à marginaliser le travail sur le son pour l’associer à l’image, la mise en scène ou la performance, Jean-Luc Hervé préfère se concentrer sur la musique, tout en étendant le champ de l’écoute musicale à d’autres situations que celle de la salle de concert. Dans le cas d’un environnement sonore pour une exposition, tout est à repenser, afin notamment de prendre en compte les caractéristiques de l’architecture et le comportement du public. Le compositeur s’est déjà frotté à des exercices similaires, avec son récent Germination, pensés pour la place Stravinsky à Paris où est sis l’Ircam, ou Amplification/résonance pour le Musée de la communication à Berlin.

Pour Biotope, l’un des objectifs premiers a été de faire disparaître tout le dispositif de diffusion – ce qui implique une collaboration, très en amont, avec la scénographe de l’exposition. « Plutôt que de créer un espace virtuel artificiel, remarque Jean-Luc Hervé, le projet est au contraire de souligner par une proposition musicale l’espace réel que nous arpentons ; ici celui de la galerie 4 du Centre Georges Pompidou. »

Pour Biotope, l’un des objectifs premiers a été de faire disparaître tout le dispositif de diffusion – ce qui implique une collaboration, très en amont, avec la scénographe de l’exposition. « Plutôt que de créer un espace virtuel artificiel, remarque Jean-Luc Hervé, le projet est au contraire de souligner par une proposition musicale l’espace réel que nous arpentons ; ici celui de la galerie 4 du Centre Georges Pompidou. »

La solution trouvée a été de parsemer l’ensemble de la galerie de multiples sources sonores très localisées, dans les murs ou sous le mobilier de l’exposition. Le son a une présence physique : on pourrait presque le toucher, mais son origine reste invisible. « Mon travail (peut-être comme alternative à la virtualisation de notre monde quotidien) s’intéresse en général à la présence des sons, et propose une écoute de la musique qui se diffracte en de multiples points clairement localisés. » Le niveau de diffusion est assez faible donnant l’impression d’un dialogue entre les individus d’une population de petits animaux (batraciens, insectes ou oiseaux) qui se cachent dans l’architecture. Chaque agent sonore de cette population a son autonomie (grâce à un ordinateur doté d’une “proto-intelligence” artificielle) qui interprète à sa manière et en temps réel la forme sonore (le chant) caractéristique de la population. Des capteurs permettent quant à eux au dispositif de réagir à la présence et aux mouvements des visiteurs.

1. Anne Cauquelin, Jean-Luc Hervé, Les Jardins de l’écoute, éditions MF.

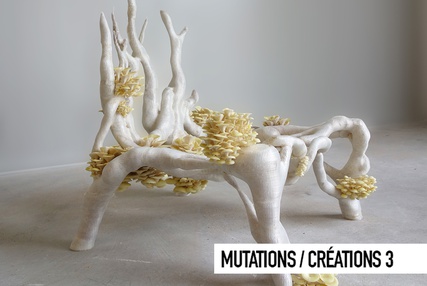

Images

1. et 2. Ginsberg Alexandra Daisy, Agapakis Christina, Sissel ToolasThe Sublime Hibiscus Landscape (image 1) et The Sublime Hibiscus Portrait (image 2), 2018-2019

Resurrecting the Sublime: reconstruction numérique du spécimen disparu, Hibiscadelphus wilderianus, du versant sud du mont Haleakala, sur l’île de Maui, à Hawaï.

© Gray Herbarium of Harvard University © Christina Agapakis of Ginkgo Bioworks, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg & Sissel Tolaas

3. Exposition « La Fabrique du Vivant », Centre Pompidou. Resurrecting the Sublime: Hibiscadelphus wilderianus Rock (hotte à diffusion olfactive, bloc de lave, documentaire, Février 2019.

Biographie

Jean-Luc Hervé

Compositeur

Jean-Luc Hervé fait ses études au Conservatoire national supérieur de musique de Paris avec Gérard Grisey (premier prix de composition). Sa thèse de doctorat d’esthétique ainsi qu’une reche…