Présenté du 4 octobre 2024 au 2 février 2025 à la Serpentine North Gallery de Londres au sein d’une exposition monographique consacrée au duo d’artistes Holly Herndon et Mat Dryhurst, The Call se manifeste sous la forme de deux installations parfaitement symétriques séparées par un rideau. Dans chacune d’elle, un micro suspendu au plafond offre aux visiteur.euse.s la possibilité de générer par leurs propres chants, improvisés ou non, un hymne dans le plus pur style choral sacré britannique. Réalisée en grande partie grâce à l’apprentissage profond sur une vaste base de données entièrement produites pour l’occasion, The Call se veut aussi une réflexion toute aussi profonde sur l’IA et ses implications dans la société en général.

Pour ce second volet, place à la recherche, avec Nils Demerlé, jeune doctorant ACIDS (Artificial Creative Intelligence and Data Science) auprès de Philippe Esling, au sein de l’équipe Analyse et synthèse des sons de l’Ircam, qui a développé le modèle de génération de chœur pour cette installation.

Pour ce second volet, place à la recherche, avec Nils Demerlé, jeune doctorant ACIDS (Artificial Creative Intelligence and Data Science) auprès de Philippe Esling, au sein de l’équipe Analyse et synthèse des sons de l’Ircam, qui a développé le modèle de génération de chœur pour cette installation.

Comment ce projet artistique s’inscrit-il dans le cadre de vos recherches scientifiques ?

Nils Demerlé : Il se trouve que, lorsque Holly et Mat sont venus nous trouver à l’Ircam, j’avais déjà un peu travaillé sur la génération de chœurs, dans le cadre des concerts que l’équipe ACIDS organise régulièrement, pour montrer ce dont sont capables les modèles que nous développons. Le modèle sur lequel je travaillais faisait déjà du « transfert de timbre » qu’on appelle plutôt, dans le cas beaucoup plus complexe d’un chœur tout entier, « transfert de style ». À l’origine, ce modèle n’était capable que de projeter un son de chorale sur un autre son de chorale – et en temps différé. Holly et Mat m’ont cependant assez rapidement demandé d’imaginer un autre modèle qui n’aurait besoin que d’une voix solo en entrée, et qui fonctionnerait de manière interactive.

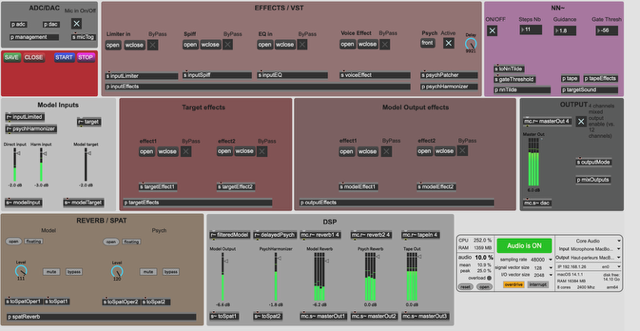

Aujourd’hui, le modèle génère donc un chœur artificiel sur la base de deux flux audios en entrée : l’un définissant la cible en termes de timbre et d’harmonie (un segment de 5 à 10 secondes – en pratique, c’est le son de chœur qui sert d’environnement sonore à l’installation), l’autre permettant d’extraire des hauteurs, des rythmes et des paroles (en pratique : la voix du/de la visiteur.euse). Le tout en temps réel, ou tout du moins avec une latence d’environ 300ms. Cette latence nous oblige à générer plutôt un discours en forme de questions/réponses, au reste très proche du chant choral traditionnel. Quand un.e visiteur.euse chante dans le micro, son chant est ainsi aussitôt rediffusé, dans le même ton choral que l’environnement sonore auquel il se mêle.

Le patch final, qui tournera au sein d’un environnement Max grâce au plug-in nn~, doit beaucoup à RAVE (pour « Realtime Audio Variational autoEncoder »), un outil développé par Antoine Caillon, au sein de l’équipe ACIDS.

Quels ont été les principaux défis que vous avez dû relever ?

N.D. : Le plus grand défi a été l’exploitation des données. Mais ça a aussi été le plus intéressant pour nous. Holly et Mat ont enregistré une quinzaine de chorales à travers le Royaume-Uni. Pour chacune, nous avons eu accès aux micros-cravates individuels des chanteur.euse.s en plus de la chorale toute entière. C’est absolument parfait pour entraîner la machine à produire un son de chœur à partir d’une voix seule, puisque, dans un chœur, toutes les voix solos se retrouvent dans l’ensemble. Nous disposions également, selon les pièces, d’une dizaine, voire d’une quinzaine de prises. Seulement, toutes les chorales n’avaient pas enregistré tous les morceaux, et nous avions besoin d’une grande quantité de matériau. Nous avons donc aussi récupéré les enregistrements de leurs échauffements et de leurs exercices.

D’autre part, ce sont tous des chœurs amateurs – avec leurs défauts. Certain.e.s choristes ne chantent pas toujours très justes. Et la qualité des enregistrements n’était pas toujours idéale. Devait-on tout garder pour autant ? Devait-on corriger la justesse des voix (ce qui est tout à fait possible avec nos outils d’autotune) ? Si on ne les corrigeait pas, le chant généré risquait à son tour de souffrir d’une justesse aléatoire : devait-on alors la corriger après coup ? Nous avons finalement pris le parti d’écarter environ 30% des enregistrements.

D’autre part, ce sont tous des chœurs amateurs – avec leurs défauts. Certain.e.s choristes ne chantent pas toujours très justes. Et la qualité des enregistrements n’était pas toujours idéale. Devait-on tout garder pour autant ? Devait-on corriger la justesse des voix (ce qui est tout à fait possible avec nos outils d’autotune) ? Si on ne les corrigeait pas, le chant généré risquait à son tour de souffrir d’une justesse aléatoire : devait-on alors la corriger après coup ? Nous avons finalement pris le parti d’écarter environ 30% des enregistrements.

Un autre défi concernait bien sûr le fait d’inférer un chant à partir de la voix solo. La base de données comprend, les voix séparées en plus de la chorale entière, mais ce sont pour certaines des voix intermédiaires, qui ne déterminent pas nécessairement la forme globale de l’hymne. Surtout, dans les micros individuels, on entend un peu les autres voix : le modèle a donc l’habitude d’entendre le chœur entier derrière chaque voix individuelle. Nous avons donc « triché », en ajoutant un harmonizer à la voix du visiteur – la génération du chœur entier en est grandement facilitée. C’est une solution à laquelle, en tant que chercheurs, nous n’aurions jamais recours – nos articles ne passeraient jamais l’étape de la relecture par les pairs ! Cependant, dans le cadre d’une démarche artistique, nous sommes beaucoup plus libres.

En tant que chercheur dans le domaine de l’intelligence artificielle, quelle est selon vous l’originalité de la démarche d’Holly et Mat ?

N.D. : Le fait de collecter eux-mêmes le jeu de données sur lequel entraîner leur modèle, pour mieux le mettre en lumière. Voilà plusieurs années qu’ils travaillent sur des outils d’intelligence artificielle et, à chaque fois, ils ont à cœur de mettre à l’honneur les artistes qui se cachent derrière le modèle. Cette manière de faire est du reste la seule à même d’obtenir un résultat qui reproduise l’identité sonore si particulière de ces chorales britanniques.

Y aurait-il une éthique du développeur ?

N.D. : C’est une question qui me préoccupe beaucoup. Une question essentielle dans notre domaine de recherche : ai-je envie de générer de la musique d’une manière qui fait peser des menaces sur l’économie de la filière toute entière ? Comment rémunérer les artistes qui ont produit toutes ces données ? Doit-on d’ailleurs parler de « données » dans ce cas ? Ce projet a plutôt renforcé mes convictions. Voilà bien longtemps que je m’interdis d’entraîner des modèles sur des jeux dont je n’ai pas des droits, et ce n’est pas aujourd’hui que je vais commencer. Au reste, je considère que les outils que nous développons ici sortent un peu du cadre problématique d’autres outils génératifs, à l’instar de ChatGPT. Je les vois plus comme des instruments à la disposition des créateurs que comme des générateurs de musique au kilomètre.

Dernier point, et non des moindres : la méthode et le code que je développe, qui permettent d’entraîner le modèle sur les données réunies par Holly et Mat, seront intégralement publiés et accessibles gratuitement sur Internet.

Propos recueillis par Jérémie Szpirglas

Photo 1 : Nils Demerlé © Ircam-Centre Pompidou, photo : Déborah Lopatin

Photo 3 : Les doctorants David Genova et Nils Demerlé © Ircam-Centre Pompidou, photo : Déborah Lopatin