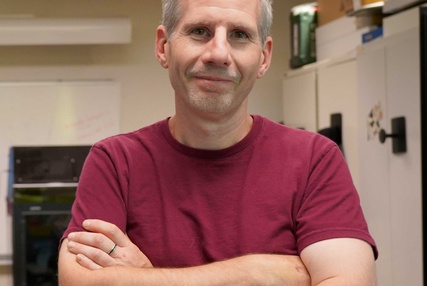

Pour accompagner sa résidence en recherche artistique à l’Ircam autour de la captation de mouvement associée à des processus de synthèse et de composition, Basile Chassaing a fait appel à la chorégraphe Emmanuelle Grach. Interprète et chorégraphe formée au Conservatoire de Paris auprès de Susan Alexander, Peter Goss et Joëlle Mazet, Emmanuelle Grach fonde en 2009 sa propre compagnie Nevermind. Elle collabore également avec Hervé Robbe au sein de sa compagnie Travelling & Co ainsi qu’avec l’Ensemble Le Balcon, notamment dans le cadre de ses projets autour de l’opéra Le Balcon de Peter Eötvös (d’après l’œuvre de Jean Genet), ou de l’opéra monstre Licht de Stockhausen. Nous l’avons rencontrée au cours d’un atelier dans le studio 3 de l’Ircam, et avons par la suite pris le temps d’échanger.

D’abord et avant tout, comment cette collaboration avec Basile Chassaing est-elle née ?

D’abord et avant tout, comment cette collaboration avec Basile Chassaing est-elle née ?

J’ai rencontré Basile par l’intermédiaire d’Hervé Robbe, chorégraphe et directeur du pôle Création chorégraphique de la Fondation Royaumont. Je ne savais alors rien de son travail mais il m’a parlé de son envie d’inclure un processus chorégraphique en parallèle de la création musicale et électronique.Ayant déjà collaboré étroitement avec des musiciens et des compositeurs dont le cheminement créatif et/ou d’interprétation accordait une place prépondérante à la danse (notamment avec la Fondation Stockhausen et l’Ensemble Le Balcon), cela m’a tout de suite parlé et nous avons commencé à travailler ensemble.

Qu’est-ce qui vous a séduit dans ce projet en particulier ?

Ce qui m’a attiré, c’est le dispositif qu’utilise Basile. Ce sont des capteurs placés au niveau des mains, qui influencent le son en fonction de leur déplacement dans l’espace. J’étais très curieuse à l’idée de chorégraphier avec ce dispositif, qui représente tout à la fois un atout et une contrainte.

Ce projet, par sa nature même, aspire à inverser le paradigme musique/danse (selon lequel, dit simplement, la danse suit ou, du moins, est ponctuée temporellement, par le discours musical)…

C’est justement ce que l’on voulait explorer avec Basile. Comment amener un geste chorégraphique qui doit avoir du sens mais qui va aussi influencer l’écriture musicale ? L’un ne doit pas prendre le pas sur l’autre mais, en même temps, il faut bien commencer quelque part. Ce qui exige de trouver un équilibre entre création musicale et création chorégraphique.

Connaissez-vous ce qui s’est déjà fait (à l’Ircam ou ailleurs) dans ce domaine de la captation de geste utilisée chorégraphiquement en même temps que musicalement ?

J’ai pu tester d’autres dispositifs musicaux. Notamment avec Michelle Agnes Magalhaes lors d’une semaine d’ateliers au Centre national de la danse (CND) de Paris, au cours de laquelle j’assistais Michelle Agnès et Hervé Robbe dans leurs échanges avec un groupe de jeunes danseurs.

J’ai également rencontré Jean Geoffroy et Christophe Lebreton lors d’un laboratoire chorégraphique organisé à la Fondation Royaumont.

Comment se passe l’exploration de l’outil ensemble ? Comment vous l’appropriez-vous chorégraphiquement ?

La première phase de travail avec Basile a consisté à tester le dispositif afin de déterminer ses réactions à nos gestes et évaluer sa sensibilité. Nous avons filmé les essais et cela a fourni à Basile une base de données pour chercher et tester de son côté. Quant à moi, cela m’a permis de constater l’étendue des possibles ouverts par le dispositif et de réfléchir comment les intégrer corporellement.

La deuxième phase a été consacrée aux choix dramaturgiques pour imaginer les modes d’utilisation du dispositif au service d’un propos. Le dispositif exige en effet des danseurs une énergie phénoménale et une vitesse de mouvement assez élevée. Ce qui nous a amenés à explorer les spasmes, la respiration… mais aussi le courant électrique, la transmission d’informations et l’intelligence artificielle…

La troisième phase – la création proprement dite – a été initiée dans le cadre d’une résidence à Royaumont, avec danseurs et musiciens. Deux pistes ont été explorées afin de créer avec le dispositif.

Première piste : faire ce qu’il faut pour produire du son. C’est-à-dire « bouger » les mains d’une manière particulière pour provoquer du son. Un dialogue est alors né entre les deux danseurs, que nous arrivions même à identifier de part « leurs voix », ou « leurs sons », propres – déterminés par la nature de leurs gestes. Ainsi sont apparus de véritables personnages !

La deuxième piste consiste à créer en faisant abstraction des capteurs. À chorégraphier sans se laisser influencer par ce que provoque un geste du point de vue sonore. Bien entendu, cela a pu se faire car la musique de Basile laisse de la place pour l’improvisation et le hasard.

Y a-t-il des aspects qui vous attirent davantage, des champs que vous voudriez explorer plus particulièrement ?

Nous avons pensé à un moyen d’élaborer un discours parlé avec ce capteur grâce à une intelligence artificielle. L’IA est un sujet qui m’attire beaucoup et je suis sûre qu’il y a plein de choses à tester avec !

Qu’en attendez-vous dans le cadre de votre pratique ?

Comme chaque projet, j’en sors avec de nouvelles approches, de nouvelles manières, d’écouter, de créer… Mon travail se nourrit forcément de tous les projets auxquels je participe. Avec Spa(s)m, mon écoute musicale et mon travail de collaboration avec les musiciens et/ou compositeurs ont été enrichis. Avoir pu assister au processus de création de Basile m’a permis d’observer et analyser comment s’élabore une partition musicale et comment elle évolue.

Propos recueillis par Jérémie Szpirglas

Crédits photos Olivier Allard

D’abord et avant tout, comment cette collaboration avec Basile Chassaing est-elle née ?

D’abord et avant tout, comment cette collaboration avec Basile Chassaing est-elle née ?