Chercheuse au sein de l’équipe Espaces acoustiques et cognitifs, Isabelle Viaud-Delmon est responsable scientifique au sein de l’axe Son, Musique & Santé du laboratoire STMS. Elle fut aussi la co-directrice de thèse de Vincent Isnard et l’accompagne à nouveau dans le cadre de cette résidence en recherche artistique menée avec son frère Laurent Corvalán Gallegos.

Isabelle Viaud Delmon © Deborah Lopatin

Cette résidence en recherche artistique de Vincent Isnard et Laurent Corvalán Gallegos s’inscrit dans l’axe Son, Musique & Santé, récemment officialisé par le Haut Conseil de l’évaluation de la recherche et de l’enseignement supérieur (Hcéres), et dont vous êtes la responsable. De quoi s’agit-il ?

Ces dernières années, nous avons collectivement pris conscience du fait que nos équipes de recherche sont nombreuses à travailler à des applications plus ou moins liées au domaine de la santé. Nous avons donc souhaité mutualiser nos forces et formaliser un axe transversal à toutes les équipes du laboratoire STMS. Cet axe est soutenu par le CNRS, ce qui a notamment permis le recrutement d’une ingénieure d’étude spécifiquement affectée.

Le lien entre son, musique et santé n’a-t-il pas déjà été exploré ?

De nombreuses recherches soulignent les effets de la musicothérapie, mais les travaux menés ne permettent malheureusement pas de tirer des conclusions car il est difficile d’isoler un seul facteur en jeu. Le choix du type et des modalités de l’intervention musicale est un point d’achoppement. Le rôle de l’intervenant est essentiel, les personnalités ne sont pas interchangeables. Enfin, les protocoles sont très longs à mener. Les études sont donc difficilement comparables entre elles et les preuves ne sont finalement pas si nombreuses.

Je pourrais toutefois citer le projet mené par Séverine Sanson, à l’Université de Lille, qui s’intéressait à des personnes âgées touchées par des démences, pour comparer l’effet des interventions musicales en direct et en vidéo – avec le même intervenant, la même musique, le même discours et le même fond visuel, afin de garantir des résultats rigoureux. C’est une étude très complète, accompagnée de tout un panel de mesures de l’engagement socio-émotionnel et moteur, et qui incluait un groupe contrôle pertinent. Les analyses ne sont pas finies mais une conclusion générale s’est imposée : l’intervention en direct a eu plus d’impact que celle en vidéo.

Qu’est-ce qui distingue cette résidence en recherche artistique de ces autres études ?

L’un des grands questionnements soulevés par Vincent Isnard et Laurent Corvalán Gallegos repose sur la dualité entre une pratique artistique et une pratique de bien-être. C’est une question complexe, mais, n’étant pas spécialiste, je n’ai pas les outils pour y répondre et, pour tout dire, même s’il est pour moi important que cette pratique soit artistique, ce n’est pas la question qui m’anime.

Cependant, on constate que la grande majorité des diplômes qui existent dans le domaine de la musicothérapie en France se font dans le cadre d’une université de médecine ou de pharmacologie ou d’un établissement de santé – et font donc l’impasse sur le niveau musical d’excellence que cela exige. Selon moi, ces filières devraient exister aussi dans les conservatoires.

C’est d’ailleurs un des aspects qui m’a immédiatement séduite dans le projet de Vincent et Laurent : ce sont tous deux des artistes de très haut niveau, qui s’appuient avant tout sur leur pratique artistique. Il serait du reste très intéressant, d’un point de vue scientifique, de voir leurs expériences, avec le même protocole, menées par des intervenants qui n’auraient pas la même exigence dans la démarche esthétique.

Outre cette exigence artistique, qu’est-ce qui a retenu votre attention sur ce projet ?

D’abord, il adresse parfaitement la problématique de l’interaction entre perceptions tactile et auditive, interaction que nous étudions de près dans le cadre de nos travaux sur l’intégration multisensorielle, et que nous aimerions encore approfondir.

Ensuite, Vincent et Laurent proposent d’établir une sorte de catalogue de sons propices à promouvoir le bien-être – une proposition idéale dans la perspective de l’axe Son, Musique & Santé.

Ce genre de catalogue n’existe-t-il pas déjà ?

Pas vraiment. Pas de ce type-là exactement, du moins : c’est-à-dire un corpus de sons agréables, qui ne charrient pas nécessairement d’autres sémantiques, et surtout un corpus de sons spatialisés, par l’informatique ou par l’humain. En l’occurrence, dans le cadre de la pratique développée par Vincent et Laurent, aucun son n’existe en l’absence d’espace.

D’autre part, le principe du catalogue implique aussi de proposer une catégorisation des sons, sur des critères pertinents, ce qui permettra de réfléchir ensuite à d’éventuelles propositions de soins, adaptées à des besoins spécifiques, et basées sur cette pratique artistique. Dit simplement : quels sons pour quels effets ?

Ce projet de recherche artistique s’inscrit-il dans la continuité de travaux antérieurs de l’équipe Espaces acoustiques et cognitifs ou des autres équipes de l’Ircam ?

Pas directement : la plupart des recherches que nous menons sont avant tout expérimentales – un contexte dont on sort, ici, bien entendu, pour cette résidence de recherche artistique. Mais cela va faire presque dix ans que nous étudions la façon dont la perception auditive spatiale modifie la perception tactile, et la proposition de Vincent et Laurent permet de réinvestir différemment ces travaux.

Quels sont les principaux moyens mis au service de cette recherche par l’Ircam ?

Côté technologie, Vincent et Laurent ont la possibilité d’utiliser du son spatialisé avec un rendu ambisonique, pour explorer l’idée d’enveloppe spatiale et de ses effets dans le cadre de leur pratique.

Nous contribuons aussi à la réflexion autour des enjeux expérimentaux du projet, afin de dégager les facteurs pertinents dans la perspective de valider les effets de cette pratique. Proposer, par exemple, des mises en situations susceptibles de mettre en évidence les interactions entre les différentes modalités de perception. En intégrant cette résidence en recherche artistique au sein de l’équipe qui travaille sur l’environnement sonore en trois dimensions, nous essaierons également de fournir des enregistrements spatialisés ambisoniques réutilisables par la suite, potentiellement dans le cadre d’autres études, d’autres collaborations ou d’autres perspectives de recherche.

Quel rôle tenez-vous dans le cadre de cette résidence ?

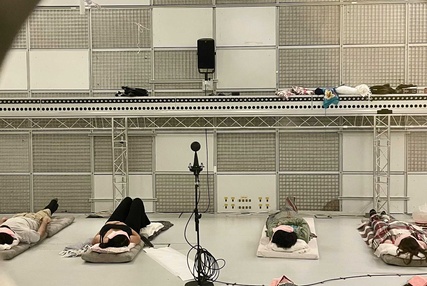

D’abord, un rôle d’observatrice, bienveillante. J’espère que mes retours sur les premières séances que Laurent et Vincent ont menées dans un contexte de soin contribueront à peaufiner le protocole en vue de la grande semaine de test prévue en septembre. Elle impliquera une soixantaine de participants (divisés en deux groupes égaux, l’un réunissant des personnes familières avec ce type de pratiques artistiques, l’autre de personnes que l’on qualifiera de « naïves »). Le protocole se doit d’être assez robuste pour garantir la fiabilité des résultats.

Quels sont selon vous les grands enjeux de cette résidence et qu’en attendez-vous ?

Ce qui m’intéresse, et je leur suis très reconnaissante de nous le permettre, c’est de pouvoir étudier une pratique de bien-être de façon scientifique. On n’a en effet aucun argument objectif pour affirmer que le son, en lui-même, peut jouer un rôle pour la santé et le bien-être – ce qu’un réinvestissement de cette pratique dans le champ de la pharmacologique exigerait pourtant. Faire accepter cette pratique et ses effets passe donc par la mise en évidence des mécanismes à l’œuvre.

J’aimerais aussi savoir si cette pratique est plus efficace dans un cadre individuel ou collectif, si la spatialisation du son a un effet – par opposition aux pratiques habituelles de sophrologie, qui passent quasi toujours par des sources fixes et localisées. Bref, étudier le principe d’intégration multisensorielle – moments sonores, moments tactiles, moments hybrides : quel est l’apport de ces trois modalités ? Et y a-t-il une potentialisation des effets si on y a recours de manière simultanée ?

On peut aussi tenter de décomposer la pratique, ou se poser la question de l’effet d’une séance sur le praticien lui-même, en sus du patient.

![]()

Propos recueillis par Jérémie Szpirglas