Depuis 2017, la dramaturge britannique Cordelia Lynn forme avec la compositrice israélienne Sivan Eldar un duo de créatrices parmi les plus fascinants de la scène musicale contemporaine. Depuis The White Princess, d’après Rilke, pour deux sopranos et percussions, créé dans le cadre de l’Académie du Festival d’Aix-en-Provence en 2017 et You’ll drown dear, pièce pour voix et électronique réalisée dans le cadre du Cursus de l’Ircam en 2017, les deux jeunes femmes sont montées en puissance avec Heave (2018), pour six voix et électronique, et s’attaquent à présent à l’opéra : c’est ainsi que l’ensemble Le Balcon créera le 21 janvier prochain à l’Opéra de Lille leur premier opéra : Like Flesh. Le duo nous raconte la genèse de cet ouvrage singulier.

De gauche à droite, la compositrice Sivan Eldar (© Léa Girardin) et la dramaturge Cordelia Lynn (© Helen Murray)

Like Flesh s’inspire en partie des Métamorphoses d’Ovide : pourquoi ? Qu’est-ce qui vous y a séduit ?

Cordelia Lynn & Sivan Eldar : Nous nous sommes rencontrées en 2016 dans le cadre l’atelier de création lyrique du festival d’Aix-en-Provence et avons depuis collaboré à un certain nombre de pièces pour voix, ensemble vocal ou chœur, dont Like Flesh est une prolongation organique. Nous nous sommes rendu compte d’un certain nombre de thèmes récurrents dans notre travail commun : l’articulation entre mondes intérieur et extérieur, la fragile lisière entre fantasme et réalité, l’amour et le désir et la solitude, la nature et ses créatures, et, bien sûr, la transformation.

C.L. : Un jour, j’ai apporté un exemplaire d’Ovide à Sivan et lui ai suggéré d’en tirer l’inspiration pour notre premier opéra. Les Métamorphoses offrent en effet un contexte propice à la discussion et à l’élaboration de nos idées et intérêts.

Like Flesh ne s’inspire donc pas d’une métamorphose en particulier ?

C.L. : J’adore le texte original d’Ovide, mais nous avons décidé de créer notre propre intrigue, un mythe contemporain de ce temps précaire qui est le nôtre, plutôt qu’une adaptation directe. Donc, non, Like Flesh n’est pas une version opératique d’un conte spécifique.

C.L. : J’adore le texte original d’Ovide, mais nous avons décidé de créer notre propre intrigue, un mythe contemporain de ce temps précaire qui est le nôtre, plutôt qu’une adaptation directe. Donc, non, Like Flesh n’est pas une version opératique d’un conte spécifique.

Sivan m’a offert l’impetus de notre version. Elle m’a demandé : « Pourquoi l’histoire devrait-elle se terminer par la métamorphose ? Ce qu’il y a de plus intéressant dans ces histoires n’est-il pas la transformation, et la manière dont les autres parviennent, ou non, à vivre avec ? » Dans un premier temps, réussir à appréhender cela au sein d’un arc dramatique a été pour moi un défi. La métamorphose représente le climax de ces mythes, c’est la raison pour laquelle on s’attend à terminer dessus. Mais c’est aussi ce qui m’a enthousiasmée, dans cette tentative d’écrire un ouvrage formellement et narrativement inattendu. C’est à la fois provocateur et dérangeant, amusant et ludique.

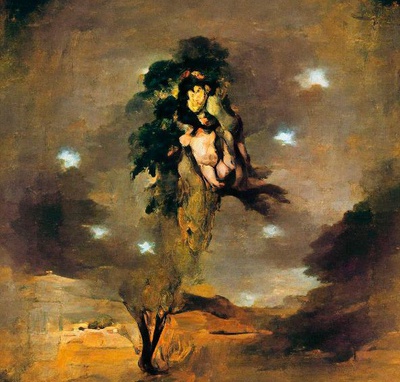

C.L. & S.E. : Très tôt, nous avons voulu nous concentrer sur les mythes concernant les arbres, pour raconter l’histoire d’un arbre et les relations que les humains peuvent nouer avec cet arbre. La distinction entre l’humain et l’extra-humain paraît très fluide dans les Métamorphoses et cette fluidité nous a intriguées. Like Flesh parle de destruction environnementale, mais aussi de notre propre relation destructrice avec notre environnement, et de la manière dont nous sommes capables ou non de survivre dans un monde endommagé. Par conséquent, raconter une histoire d’amour, à propos des relations de l’humain avec un arbre, paraissait un moyen évident, sinon légèrement subversif, de décrire tout cela.

Destruction environnementale et histoire d’amour… L’un des thèmes principaux des Métamorphoses est le viol. Le fait que le viol soit une malédiction « intemporelle » n’est hélas pas une surprise, mais on ne peut s’empêcher de songer que ce thème ainsi considéré résonne d’un formidable écho (tiens, encore une métamorphose) dans notre société contemporaine : cela a-t-il pesé dans la balance pour choisir le sujet de votre opéra ?

C.L. & S.E. : Chez Ovide, les femmes n’ont pas vraiment le choix quant à leurs métamorphoses. Elles vaquent à leurs occupations, vivent leurs vies, et soudain un homme ou un dieu surgit qui tente de les violer. Elles appellent à l’aide et d’autres dieux résolvent la situation en les transformant en arbre ou tout autre chose, alors qu’il aurait sans doute été plus judicieux de transformer l’agresseur en pierre. Ce sont des histoires anciennes, mais il est utile de mentionner que, en mars 2020 au Royaume-Uni, seul 1,6% des plaintes pour viol enregistrées par la police se terminait en poursuite, et encore moins en condamnation. Inutile d’expliquer les liens qu’il y a ici.

Toutefois, Like Flesh ne traite pas directement de ces histoires de viol. Il y a de nombreuses raisons pour les métamorphoses chez Ovide. La terreur, oui, mais aussi la passion, l’amour, la douleur, la rage, la honte… Une autre manière d’interpréter les Métamorphoses est que certaines émotions peuvent être si fortes, si puissantes, que notre enveloppe mortelle est incapable de les contenir, et explose en quelque chose d’Autre. Dans notre cas, c’est la passion, l’amour, le désir, qui provoquent la transformation de la Femme en Arbre, et cela se déroule dans un contexte clairement consensuel.

Comment vous êtes-vous appropriées ces mythes ? Quels aspects avez-vous souhaité mettre en avant ?

C.L. : Quand j’écris, je passe des mois à lire, à regarder, à écouter, tous azimuts autour du projet. Avec Like Flesh, j’ai fait des recherches sur les arbres et les forêts, sur les champignons et les réseaux mycorhiziens, sur les comportements reproductifs des plantes, sur les formes anciennes et modernes d’agroforesterie, sur le savoir traditionnel en comparaison avec l’approche scientifique occidentale de l’écologie… Et j’ai beaucoup lu au sujet de destruction environnementale, et particulièrement de son impact émotionnel et psychologique. Je me suis intéressée aux concepts d’éco-anxiété et de « solastalgie », qui sont des concepts philosophiques décrivant une forme de trouble nostalgique que l’on peut ressentir au sujet d’un lieu qui existe encore, mais altéré par les activités humaines telles que la déforestation et l’exploitation minière, au point de devenir méconnaissable. La Femme, dans notre histoire, souffre de ces troubles dès l’ouverture de l’opéra.

C.L. : Quand j’écris, je passe des mois à lire, à regarder, à écouter, tous azimuts autour du projet. Avec Like Flesh, j’ai fait des recherches sur les arbres et les forêts, sur les champignons et les réseaux mycorhiziens, sur les comportements reproductifs des plantes, sur les formes anciennes et modernes d’agroforesterie, sur le savoir traditionnel en comparaison avec l’approche scientifique occidentale de l’écologie… Et j’ai beaucoup lu au sujet de destruction environnementale, et particulièrement de son impact émotionnel et psychologique. Je me suis intéressée aux concepts d’éco-anxiété et de « solastalgie », qui sont des concepts philosophiques décrivant une forme de trouble nostalgique que l’on peut ressentir au sujet d’un lieu qui existe encore, mais altéré par les activités humaines telles que la déforestation et l’exploitation minière, au point de devenir méconnaissable. La Femme, dans notre histoire, souffre de ces troubles dès l’ouverture de l’opéra.

Je pensais écrire un livre au sujet de la destruction environnementale, en utilisant en guise de métaphore une intrigue de triangle amoureux, une relation entre un homme et un arbre et une jeune femme. Mais, à mesure que j’écrivais, les deux thèmes se sont entremêlés au point que je ne suis plus certaine de ce qui est l’objet, et de ce qui en est la métaphore. Ne serait-ce pas plutôt un opéra au sujet de l’amour, utilisant la destruction environnementale comme métaphore ? Ou est-ce l’inverse, le concept originel ? Ou les deux en même temps, se travaillant l’un l’autre ? Cette ambiguïté est importante à mes yeux.

Comment avez-vous « actualisé » les mythes d’Ovide ?

C.L. & S.E. : L’intrigue est très simple : un triangle amoureux. Seulement, l’une des membres de ce triangle se transforme en arbre… Les humains qui l’aiment sont son mari (manque de chance, c’est un forestier) et une étudiante, qui loge avec eux dans leur forêt afin d’entreprendre des recherches. Formellement, la pièce est une série de scènes, entrecoupée par le chœur des arbres, La Forêt. Nous avons voulu faire ainsi référence au chœur du théâtre grec antique, en même temps qu’aux mythes grecs qui sont au cœur des contes d’Ovide. Le chœur dit la création de notre monde, tel qu’il a été façonné après la fonte du dernier âge de glace, et sa destruction au fil de 10.000 années vers un futur dévasté. Inversement, les scènes sont intenses et intimes, mettant aux prises les sentiments et les peurs et les désirs des personnages. À cet égard, cet opéra se déroule à la fois à l’échelle épique et à l’échelle humaine, tout comme les Métamorphoses d’Ovide.

Quel est votre sentiment au sujet de l’engagement de l’artiste dans la société et du rôle de l’art ?

C.L. : De plus en plus cynique.

S.E. : Les artistes font souvent partie de ceux qui portent un regard extérieur sur la société. Le rôle de leur art est de la réfléchir. Mais pas de la refléter. Nous tentons de créer des univers en explorant de nouvelles émotions, et en offrant analyses et perspectives. Les histoires que nous racontons, les univers que nous bâtissons, sont aussi variées que les sociétés auxquelles nous prenons part.

Avez-vous délibérément cherché à vous emparer de sujets politiques ou sociétaux ? Si oui, avez-vous le sentiment que cela aura un impact sur le monde comme il va ?

C.L. : Pour tout dire, je trouve toujours cette question un peu étrange, car les sujets politiques et sociétaux se manifestent dès la commande. Quelles personnes auront la chance de produire l’œuvre et pourquoi ? Voilà la première question. Et la deuxième question, c’est : quel genre d’œuvre auront-elles le droit de produire ? Par conséquent, la politique et la société affectent déjà le processus, et vice versa, avant même d’avoir commencé à écrire. Mon avis personnel, c’est que toute idée d’un « art » comme quelque chose de pur et d’abstrait est systématiquement idiot, voire malhonnête.

D’un autre côté, je ne me donne pas pour objectif de départ de traiter des sujets politiques ou sociétaux, je ne me mets pas à ma table de travail en pensant : « Voilà un sujet brûlant, je vais écrire là-dessus. » L’exécution importe autant pour moi que le sujet, la forme autant que le contenu. La manière de raconter une histoire est aussi éloquente que ce que l’on dit. Mais il y a bien des manières de faire du théâtre, et je ne suis pas réellement d’avis que certaines sont « meilleures » que d’autres. Il faut des œuvres de natures très variées pour générer une culture diverse et saine, et une culture diverse et saine aura un impact sur la société.

Propos recueillis par Jérémie Szpirglas

Visuel 2 et 3 : © Francesco D'Abbraccio