Maître de conférences à Sorbonne Université et chercheur au sein du laboratoire Sciences et Technologies de la Musique et du Son à l’Ircam, Nicolas Obin travaille sur la synthèse vocale depuis plus de dix ans. Spécialiste du traitement de la parole et de la communication humaine, il poursuit ses recherches sur l’application des dernières avancées de l’intelligence artificielle (IA) à la voix et à ses technologies. Il travaille aussi bien avec les experts du SCAI (le Centre d'Intelligence Artificielle de la Sorbonne) qu’avec des artistes de renom dans le cadre de son engagement artistique à l'Ircam, tels que Eric Rohmer, Philippe Parreno, Roman Polansky, Leos Carax, Georges Aperghis ou encore Alexander Schubert cette année. Nous le rencontrons à l’occasion du festival ManiFeste-2022, pour lequel il organise les rencontres « Deep Voice, Paris » qu’il a co-fondées avec Xavier Fresquet du SCAI.

À l’heure de l’IA, du deep learning et des assistants vocaux, l’Ircam se place comme un pionnier en matière de création de voix de synthèse. Nicolas, peux-tu nous en dire plus sur l’objet des recherches que tu mènes au quotidien dans l’équipe Analyse et synthèse des sons ?

Avec les assistants vocaux, la voix s’est imposée comme une modalité privilégiée d’interaction de l’humain avec les machines connectées de son environnement quotidien. La voix permet en effet d’animer la machine et de lui donner une apparence d’humanité. Mes recherches portent principalement sur la modélisation numérique de la voix humaine à l’interface de la linguistique, de l’informatique, de l’apprentissage machine et de l’intelligence artificielle. L’objectif est de mieux comprendre la voix et la communication humaine pour créer des machines douées de parole, cloner l’identité vocale d’une personne ou d’en manipuler les attributs de personnalité comme l’âge, le genre, les attitudes, ou les émotions.

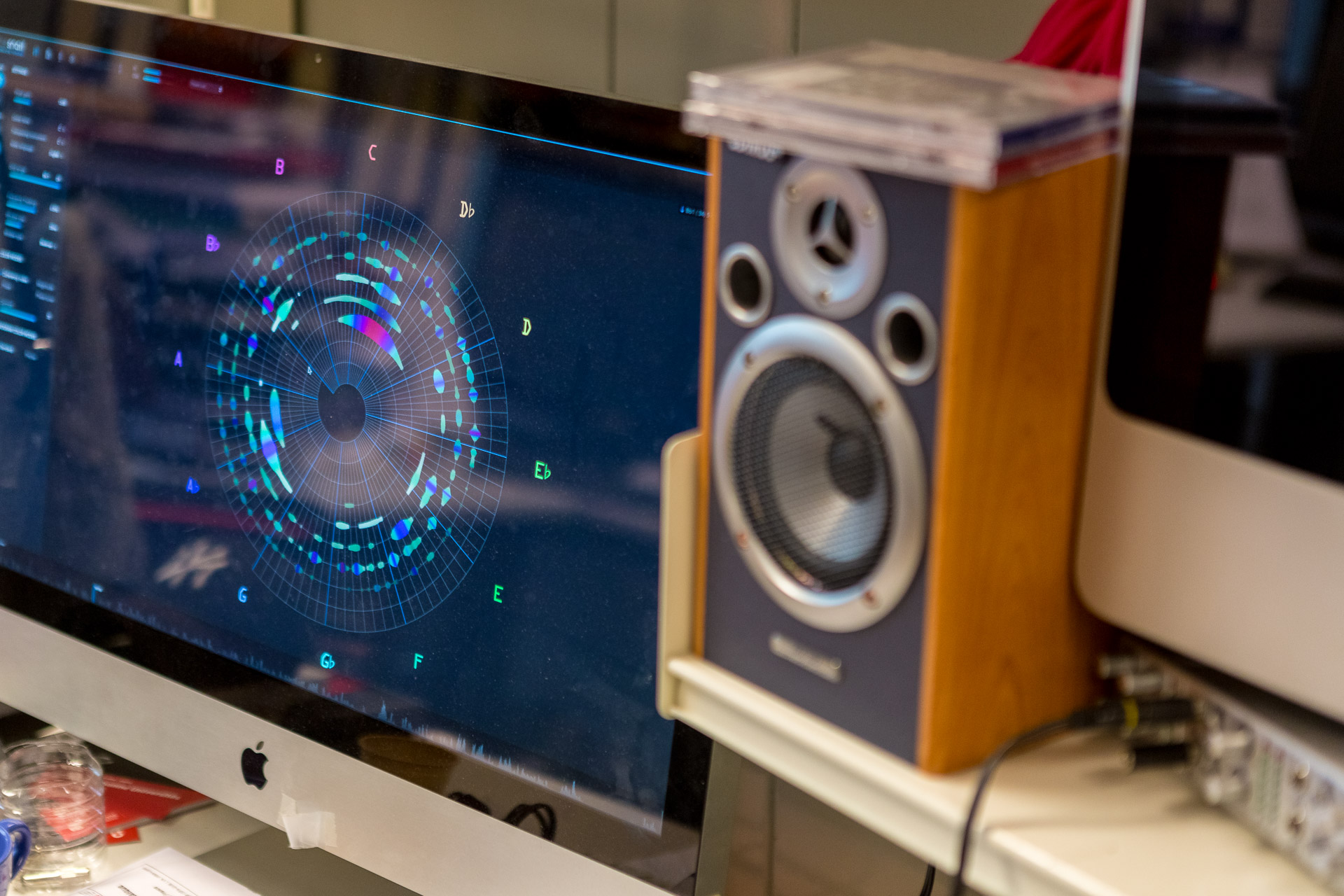

Notre équipe, dirigée par Axel Roebel, a une grande expertise scientifique et technologique sur la voix humaine, notamment en transférant nos avancées de recherche dans des plugins audio professionnels dédiés à la voix comme IrcamTools TRAX ou IrcamLab TS qui sont régulièrement utilisés par les sound designers au cinéma. Le sound designer Nicolas Becker a par exemple utilisé les fonctionnalités du logiciel IrcamLab TS pour recréer la sensation de la perte progressive de l’audition dans le film Sound of Metal pour lequel il a reçu l’Oscar de la mise en son.

Outre les collaborations artistiques, nous travaillons également en permanence avec des marques et des entreprises pour conférer une voix artificielle à des assistants personnels, des agents virtuels, ou des robots humanoïdes.

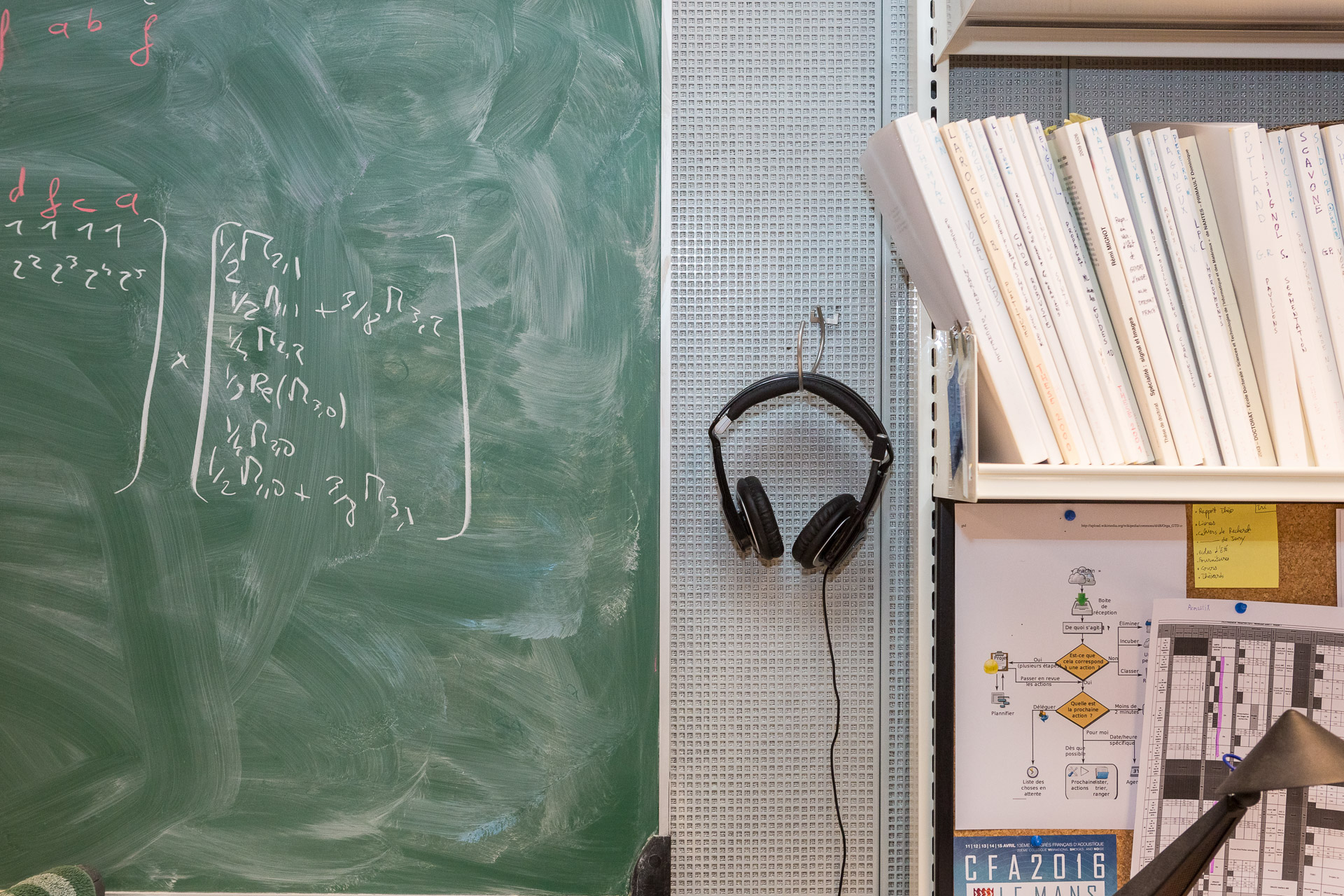

Laboratoire Analyse et synthèse des sons à l'Ircam © Philippe Barbosa

Tu es le co-fondateur des rencontres « Deep Voice, Paris » un événement annuel dédié à la voix et à l’intelligence artificielle qui se tient cette année du 15 au 17 juin 2022. Quel sera l’objet des débats de cette 2e édition ?

La thématique qui anime cette seconde édition est la diversité et l’inclusion dans les technologies vocales pour un monde numérique mieux personnalisé et plus représentatif de la diversité des individus, des cultures, et des langues. Si l’on observe aujourd’hui entre 6000 à 7000 langues vivantes dans le monde – dont la langue des signes –, seulement quelques dizaines, une centaine au mieux, sont présentes dans le monde numérique, que ce soit dans les moteurs de recherche, pour la traduction ou les assistants vocaux. L’objectif des « Deep Voice, Paris » est de rassembler les acteurs de le recherche scientifique et de l’innovation technologique pour imaginer les usages et les pratiques du futur, mais aussi porter une réflexion critique sur l’apport du numérique dans le monde d’aujourd’hui et de demain.

Nous aurons le plaisir d’accueillir des acteurs à la pointe de l’innovation sur ces thématiques, en particulier la première voix artificielle non-genrée réalisée par les membres du projet Q, l’initiative de science ouverte Common Voice de Mozilla, les entreprises Navas Lab Europe et ReadSpeaker spécialisées en synthèse vocale multilingues et en agents virtuels, ou encore la startup californienne SANAS qui est capable de transformer l’accent d’une personne quasiment en temps-réel ! Les rencontres « Deep Voice, Paris » offrent l’occasion de se tenir au courant des évolutions technologiques, d’en rencontrer les acteurs et de participer à la réflexion sur leurs usages dans notre quotidien.

En portant le projet ANR TheVoice tu t’es attaqué à la création de voix pour la production de contenu dans le secteur de l'industrie créative. Ce consortium de recherche appliqué a-t-il abouti à des réalisations marquantes ?

Le projet ANR TheVoice a été l’occasion pour nous de collaborer très étroitement avec les acteurs de l’industrie créative, comme des sociétés de production et de post-production, pour le doublage notamment. Il nous a donné l’occasion de mieux comprendre les métiers de la voix, les enjeux industriels et culturels, et d’y apporter des solutions d’intelligence artificielle totalement nouvelles dans un secteur particulièrement exigeant en termes de qualité.

Nous avons en particulier conçu des algorithmes permettant de transférer l’identité vocale d’une personne sur la voix d’une autre personne, en un mot un « deep fake vocal ». Nous avons déjà appliqué ces innovations, dans le cadre d’un projet conduit avec Ircam Amplify, pour la nouvelle émission de Thierry Ardisson l’« Hôtel du Temps » dans laquelle les technologies de « deep fake » sont utilisées pour redonner une vie numérique à des personnalités le temps d’une interview ; pour recréer la voix d’Isaac Asimov, l’un des fondateurs de la science-fiction, dans un documentaire d’Arte en cours de production ou encore pour créer des voix artificielles dans la dernière œuvre d’Alexander SchubertAnima™ qui vient d’être présentée au Centre Pompidou dans le cadre du festival ManiFeste.

Et du côté de la recherche fondamentale, quels sont les enjeux pour la création des voix du futur, les derniers défis à relever par les chercheurs ?

L’essor de l’intelligence artificielle au milieu des années 2010 a provoqué des progrès extrêmement spectaculaires dans l’ensemble des domaines du numérique et en particulier des technologies vocales. En 2018, furent créées les premières voix artificielles jugées aussi naturelles que les voix humaines et cet aboutissement a permis de franchir le seuil d’une sorte de « singularité vocale ». Cette première préfigure les mutations rapides et profondes liées à la modélisation et la simulation d’humains digitaux et de nos modes d’interactions avec les machines, dans une immersion toujours plus grande dans le numérique. Mais, malgré ces avancées, la voix demeure une manifestation complexe de l’être humain : par contraste avec l’animation 3D largement utilisée au cinéma, dans les jeux vidéo, ou pour la réalité virtuelle, les champs d’application de voix artificielles demeurent encore très limités.

Les prochains défis de la recherche sont nombreux : ils consistent notamment à manipuler les attributs d’une voix pour créer des filtres numériques permettant de sculpter la personnalité d’une voix humaine ou artificielle, à améliorer la modélisation de la voix en interaction, en particulier avec son contexte, pour permettre une interaction vocale fluide, personnalisée et adaptée à un interlocuteur et à une situation, le tout de manière ultra-réaliste, possiblement guidé par la physique… et en temps-réel !

Ce foisonnement de recherches et d’innovations constitue un formidable terrain d’expérimentation pour les artistes. Ils peuvent désormais réaliser des voix et des vocalisations en quelque sorte inouïes, c’est-à-dire affranchies des contraintes de la nature et de la physique, que ce soit pour faire chanter une voix avec une tessiture inhumaine (irréalisable par un être humain) ou pour créer des objets cyber-physiques doués de voix hybrides comme pour faire parler un arbre, une lampe, ou une guitare. Autant de possibilités pour imaginer des nouvelles formes d’expression et d’artefacts sonores créatifs à l’interface de l’humain et de la machine, du singulier et de l’universel, du réel et du virtuel.