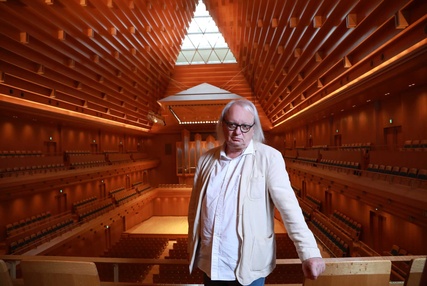

Entretien avec Philippe Manoury : réinventer l'opéra

Vous évoquez d’emblée la vaste histoire de l'opéra : quels aspects de cette tradition souhaitez-vous revisiter ou, à rebours, laisser derrière vous ?

Vous évoquez d’emblée la vaste histoire de l'opéra : quels aspects de cette tradition souhaitez-vous revisiter ou, à rebours, laisser derrière vous ?

Philippe Manoury : Je ne crois plus beaucoup à la forme traditionnelle de l’opéra. Pour les histoires d’aujourd’hui et au vu de l’évolution des publics, les codes de l’opéra traditionnel ne fonctionnent pas : pourquoi chanter certains textes plutôt que les dire ? Chanter, cela peut sublimer le propos, certes, mais si le texte est trop prosaïque, trop réaliste, ça ne passe pas. D’où l’idée que nous avons eue, Nicolas Stemann et moi-même, du « Thinkspiel », déjà avec Kein Licht en 2017. Le Thinkspiel tel que je l’envisage permet de mêler voix parlées et chantées. Les deux s’interpénètrent. Certaines situations ont parfois une importance informationnelle : il faut les comprendre pour saisir le contexte. C’était autrefois la fonction des récitatifs. D’autres sont du domaine de l’intériorisation, de la sublimation ou de la transcendance. L’expression prime alors sur les mots et leur sens. Un exemple emblématique se trouve au début du deuxième acte de Tristan, de Wagner, lorsque les deux amants se retrouvent : on ne comprend pas un mot de ce qu’ils disent – c’est peut-être mieux ainsi ! – mais le chant suffit pour transmettre l’émotion provoquée par la situation.

Comment sont nés les opéras que vous créez cette année ?

P.M. : Cela faisait longtemps que j’entendais parler de Karl Kraus. À commencer par Max Deutsch, mon professeur de composition, jusqu’à, plus récemment, le philosophe Jacques Bouveresse, probablement le plus grand spécialiste de Kraus en France. C’est en cherchant un sujet pour un nouvel opéra de grande forme que cet ouvrage s’est petit à petit imposé. Ce sujet, la guerre infinie, est toujours d’une actualité brûlante, mais ce qui m’intéressait aussi était le fait qu’il n’y a aucun personnage principal, plutôt une myriade de situations. Je trouve cela, formellement, plus excitant. Pour mettre en valeur cette dimension intemporelle et presque universelle de la guerre, j’ai conçu l’œuvre en deux parties. La première, plus historique, se tient au plus près du texte de Kraus à l’époque de la Première Guerre mondiale tandis que la seconde est sans ancrage temporel précis. Cela peut évoquer notre époque, ou peut-être nous faire pressentir le futur. L’époque importe peu, le phénomène de la guerre n’étant lié à aucune en particulier.

Quelles leçons tirées de vos précédents opéras vous ont aidé à composer celui-ci ?

P.M. : Depuis Kein Licht, j’ai abandonné la structure classique de l’opéra. Sur la forme, ce dernier était beaucoup plus ouvert. J’avais composé des modules indépendants qu’on aurait pu jouer dans un autre ordre. Le texte d’Elfried Jelinek et l’approche que nous avions adoptée avec Nicolas Stemann s’y prêtaient. Idem pour le petit ensemble instrumental, qui permettait une mobilité acceptable. Avec Die letzten Tage der Menschheit, je reviens à une forme plus structurée dès le départ. Avec un grand orchestre, il aurait été impossible d’avoir une telle mobilité. Il y aura donc des scènes plus préparées, structurées à l’avance, mais aussi des moments plus expérimentaux, comme ce théâtre électronique que je désire inventer pour l’occasion.

Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then

Qui dit opéra, dit livret. Vous avez cette fois travaillé avec un livret un peu plus construit, auquel vous avez-vous-même œuvré.

P.M. : Avec Patrick Hahn et Nicolas Stemann, nous avons en effet beaucoup retravaillé le texte de Karl Kraus qui est gigantesque. Lui-même considérait que c’était un théâtre non pas pour la Terre mais pour Mars ! À vrai dire, il n’y a pas de structures réellement dramaturgiques dans ce texte qui est une espèce de monstre à mille têtes. Beaucoup de phrases qui y figurent ne sont pas de lui mais entendues dans la rue, dans des cafés, des meetings, etc. Une sorte de préfiguration de nos réseaux sociaux.

La première partie suit les cinq chapitres du livre de Kraus, eux-mêmes correspondants aux cinq années de guerre. Au cours de la seconde partie, on s’éloigne de Kraus pour évoquer d’autres situations, plus contemporaines, mais on revient à Kraus vers la fin. La conclusion, apocalyptique, reprend celle du livre : constatant que l’humanité a détruit toute chance de survie pour elle-même, des êtres venus d’ailleurs la condamnent à la disparition. Je n’ai toutefois pas eu envie de terminer sur cette note grandiloquente : je vais donc refermer l’opéra sur une scène intimiste, où trois femmes incarnent le chœur des enfants qui supplient de ne pas naitre dans un tel monde. Tout cela peut sembler très noir, si ce n’est pour l’humour parodique très viennois qui circule dans ce texte.

Bien qu’il n’y ait initialement pas de personnage principal dans ce Thinkspiel, nous en avons rajouté un : « Angelus Novus », cet étrange personnage ailé peint par Paul Klee, dont le philosophe Walter Benjamin a fait une allégorie de l’Histoire. Comme c’est un ange, j’aimerais lui créer comme une « auréole sonore » autour de la voix – peut-être à l’aide d’une synthèse en temps réel, qui fera résonner son chant, mais je ne suis pas sûr d’y parvenir.

Quel rôle, d’ailleurs, peut avoir l’informatique musicale dans le dispositif opératique ?

P.M. : Le principe même du Thinkspiel suppose selon moi de faire interagir l’informatique musicale et ce qui se passe sur scène, en temps réel naturellement – voire à en extraire du matériau pour la musique électronique. Ce genre utilise la voix parlée et chantée, ce qui n’est bien sûr pas une nouveauté. Ce qui l’est, en revanche, c’est que je fais entrer les voix parlées dans le monde musical. Voilà des années que je soutiens que le parler est du chanter chaotique. Par essence, il est non stylisé, mais si on arrive à en extraire des structures musicales, des rythmes, des hauteurs, des couleurs, on peut en faire un instrument de musique.

Par exemple, la voix chuchotée est totalement bruitée et ne comporte aucune hauteur que notre oreille peut identifier. Il n’y a donc pas d’inflexions vocales possibles. Mais l’ordinateur, lui, décèle très vite des fréquences de différentes amplitudes. On peut donc récupérer cette information et utiliser ces fréquences pour créer de la synthèse sonore qui se synchronisera à la perfection avec toutes les syllabes chuchotées. On peut ainsi obtenir une très grande variété d’expressions sonores, avec des profils très différents, à partir d’une voix par définition neutre musicalement.

Toujours concernant l’aléatoire, ou du moins l’illusion d’aléatoire, j’utilise un formalisme mis au point par Miller Puckette, qui a élaboré l’environnement informatique que j’utilise. Cet outil me permet, à chaque fois que je veux donner un semblant d’autonomie à l’ordinateur dans le discours musical, de naviguer au hasard dans le discours qui vient d’être produit – comme un aléatoire qui aurait de la mémoire. Cela arrive fréquemment, pour faire vivre des textures électroniques en accompagnement du jeu théâtral et/ou musical sur scène.

Propos recueillis par Jérémie Szpirglas

![]()

Photo 1 : Le compositeur Philippe Manoury © Tomoko Hidaki

L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then

L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then

L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then

L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then

L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then

L'opéra Die letzten Tage der Menscheit de Philippe Manoury © Sandra Then